Tim Maul on Artist Keren Shavit’s “Broken Kayfabe”

2014 Light Work Artist-in-Residence Keren Shavit’s Rabbits (a.k.a. Oryctolagus Cuniculus) is part of AKIN: Keren Shavit & Eva Marie Rødbrom, the first exhibition in Urban Video Project‘s 2018-2019 curatorial program. AKIN will on view at the UVP Everson Museum of Art architectural projection venue from February 15 through March 31, 2018. Vanguard filmmakers Keren Shavit and Eva Marie Rødbrom will be present for an indoor screening of additional selections of work and a Q&A with the audience on Thursday, March 8 at 6:30pm in Watson Theater at Light Work.

UVP is a multi-media public art initiative of Light Work and Syracuse University, and an important international venue for the public presentation of video and electronic arts. For more event and exhibition information, please visit www.urbanvideoproject.com.

Given Shavit’s current exhibition with UVP, we decided to dig into our archives and share the following essay about her work, written by Tim Maul, and originally published in Contact Sheet 182: Light Work Annual 2015. Tim Maul is an artist and art writer who lives in New York, NY.

—

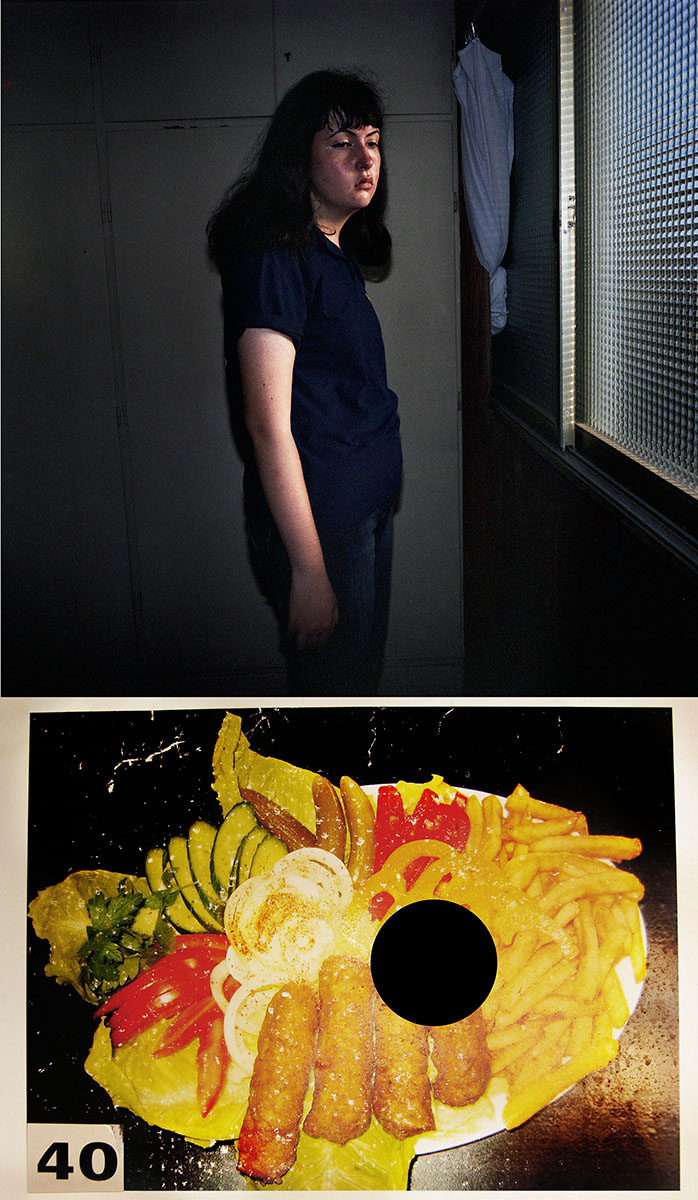

Keren Shavit’s forthcoming publication Broken Kayfabe will defy casual interpretative reading of its challenging assembly of images and text. Culled from her extensive archive of self-produced photography and video, Broken Kayfabe constitutes a metafictional tale centered on a cast of characters inhabit- ing a clique of young people working in a greasy, fast-food chain in Haifa, Israel. The ravaged individuals that populate Shavit’s images are not directed in any imposed mis en scene but function as puzzle pieces moving within a dense narrative concerning the group’s fixations on the Von Erich professional wrestling dynasty, which they fantasize joining. Peti, (“gullible” in Hebrew) the central female character, is the haunted peg this morphing story is hung upon. Her initial goal to attend the Von Erich match in Israel (an actual event) is thwarted, and she emerges as a mutable, tragic figure in a maelstrom of lurid and o en distressing photographic content. The symbols (fast- food employee cap) and markers (eating, food) dispensed throughout Broken Kayfabe are highly unstable signifiers exemplified by the Von Erichs themselves, their history fraught with deception, suicide, and internal struggles over legitimate use of the Von Erich name. Shavit has built an array of oblique documentation into a construct that, despite the seriality of any page, will deflect narrative by radically dissociating image and text.

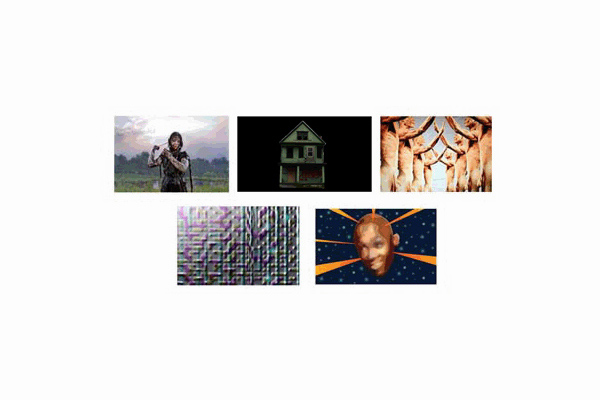

Keren Shavit, from Broken Kayfabe

Attracted to hermetic clans, Shavit courts acceptance and inserts herself into family units and social groups that o en exhibit unusual behavior or militant disregard for conventional norms. Once within, Shavit documents and mediates events captured on a battery of cameras: moving, still, and iPhone. Shavit’s project originates more from cinema than still photography, threading through the documentaries such as Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky’s Brother’s Keeper (1992) and primitivists like the Kuchar brothers, early John Waters, Harmony Korine’s Gummo, and the unsettling oeuvre of David Lynch. Lynch’s sumptuous dream film Mulholland Drive (2001) corresponds with the glamor-deprived Broken Kayfabe with its embedding of symbols like a blue key, an empty sign that, when pro red, returns the labyrinthian plotting back to mystery genre with its (false) promise of final revelations and a restoration of visual order.

Shavit’s still photographs, produced by a range of amateur technologies, are blunt and harrowing. Favoring raw texture and high contrast color, her reflexive in-camera compositions appear organized around our discomfort. While coy or voyeuristic portraiture o en maintains a self-preserving distance from its subjects, Shavit situates herself in the action located in unspecified claustrophobic settings. Unlike the supine addicted families of emaciated beautiful losers in Corrine Day’s or Jessica Dimmock’s photography, Shavit’s people, when not in repose, engage in hectic activities where aging bodies crowd into a frame awash in garish patterns amid accumulations of clutter. In both content and lurid coloration, a resemblance exists between Shavit’s images and British photographer Richard Billingham’s notorious 1996 body of work around his troubled working-class family. Billingham’s pictures cruelly recall a grotesque Monty Python skit depicting “the worst family in Britain,” with Mum ironing a cat with the son, played by fantasy director Terry Gilliam, screaming for baked beans from a couch.

Keren Shavit, from Broken Kayfabe

Shavit’s pursuit and integration with perceived outsiders are primary source material gathering repurposed, for the artist, into the unwinding tale of Peti and her circle. Scavenging her own corpus and deleting any explanatory backstory precedes an image’s enlistment into Broken Kayfabe performing a surrealist act of detournement upon her own production, and in this Shavit emerges as highly original. Shavit’s pageant of glistening bearded men, cavorting seniors, wrestlers, monstrous rabbits, and haggard fast-food employees may be interpreted as a dream world or alternative universe. Indeed, Broken Kayfabe is an amalgam of doppelgängers, tangential distractions (Hitchcock’s “MacGuns”), and enough recurring symbols to hold us in paranoid thrall. Employing multiple perspectives and imaging formats can suggest avant-garde cinema at its most hallucinatory, but I propose that Broken Kayfabe, in its structure, relates closely to the autism or Asperger’s condition, where the slippage between what is seen and what is named resists even temporal registration into contextual narrative. Individuals with these disorders may construct densely plotted, hand-rendered epics resembling storyboards or pictograph friezes not to express or communicate, but to slow reception of a delirious exterior world where language and appearance never align.

Kayfabe (pronounced kay-fabe) is a term pro wrestling insiders use for active plot, storyline, and events inside the ring. A broken kayfabe applies to an incident in the match that temporarily ruptures the fourth wall between the wrestlers and an audience that expects a continuation of the agreed action that the sport’s emotional and physical content is real. Aficionados of wrestling have detected a growing trend of these, perhaps, intentional lapses within the ring and speculate online how it will alter the future of the industry. Keren Shavit’s Broken Kayfabe project occupies a similar, convulsive space between the documented fact and the elaborate action it purports to illustrate.