A Conversation with Pacifico Silano

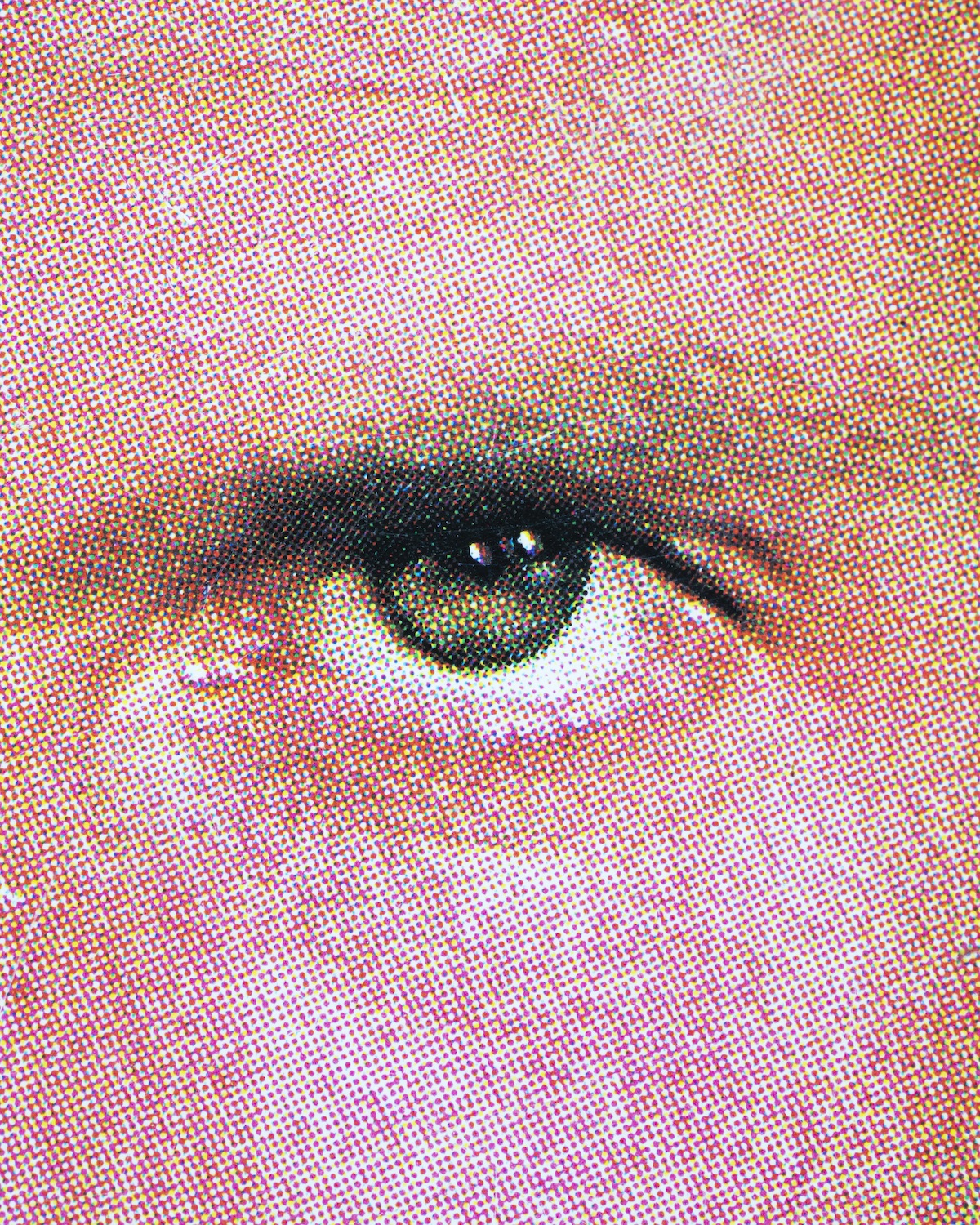

Pacifico Silano uses photographs from vintage gay pornography magazines to make colorful collages that explore print culture and the histories of the LGBTQ+ community. His works are generally large scale, evoking strength and sexuality along with the underlying repression and trauma that many marginalized individuals experience. Silano was born at the height of the AIDS epidemic and lost his uncle to HIV. After his uncle’s death, Silano’s family erased his uncle’s memory because of their own feelings of shame about his sexuality and the stigma of HIV/AIDS itself during that time. Silano set out to create art that reconciled that loss and erasure. His Light Work exhibition, The Eyelid Has Its Storms…, somberly contemplates his pain and photography’s role in the struggle for queer visibility, while celebrating enduring love, compassion, and community.

The following conversation between Pacifico Silano and Shane Lavalette, director of Light Work, has been edited for length and clarity. They spoke in 2020.

—

Shane Lavalette: Could you start by telling us a bit about your artistic practice, or perhaps more specifically, what led you to work with images through collage and appropriation?

Pacifico Silano: I started to work with appropriation while in graduate school. I was just beginning to create work around the themes of HIV/AIDS, inspired by my uncle, but didn’t have any photographs of him to work with. It really challenged me to think more broadly about the themes I was interested in exploring. I was studying under Sarah Charlesworth and Penelope Umbrico at the time. Both encouraged me to work with found imagery and I fell in love with the process of collecting materials and giving them new meaning.

SL: I gather that your family-owned an adult novelty store while you were growing up. Interesting that you’re working with vintage pornography magazines as your source material now.

PS: It sounds crazy but I always forget about the connection between the two. My parents opened the store when I was a teenager. It was something I was embarrassed to tell friends about growing up. Eventually I got over it. When I would visit home from college, my mom would have me work at the store so she could take a break. Looking back, it definitely influenced the way I think about the commodification of sex and pornography, which has very much shaped my work.

SL: I’m curious, what drew you to the particular images from the magazines? Can you talk a bit about the choice to exclude overt sexuality and nudity? Much of your work doesn’t show faces either—how do you see the individuals in the portraits?

PS: The thing I love about late 1960s through 1980s erotica is that there is a real softness to the way men are photographed. The way models are lit and the settings they’re depicted in are very particular. There’s a lot of nude bodies in the landscape captured in daylight. I like to extract those moments to meditate on loss and longing. By removing the overt explicitness and fragmenting or hiding the models, I’m asking the viewer to reconsider the photographs in a new context.

SL: I know that you’ve faced censorship of your work in the past. Most notably, in 2018, when you were asked to create a public art installation along the beach path in Bal Harbour and the city attempted to remove some of your most compelling works and redacted the word “queer” in the press release. For LGBTQ+ artists, the struggle for visibility—or simply the fight against acts of erasure—presses on. I just wonder how this experience impacted you and your artistic process and principles going forward.

PS: It was a really painful learning experience. I spent eight months working hard on something that came crashing down two weeks before it was supposed to debut. I had never had to deal with a falling out so publicly before. So it was an intense learning curve to be feuding with elected officials who had the power to shape their own narrative of what they wanted the public to think transpired. That aspect was frustrating. I’m really glad that I didn’t compromise and that I stood up for myself. The whole thing made me double down. It’s made me more committed to the work that I do.

SL: The Eyelid Has Its Storms… takes its title from a Frank O’Hara poem. Can you talk about how O’Hara’s writing had an impact on you personally, and in what ways it informs the work in your exhibition?

PS: I really love the simplicity of O’Hara’s poetry. There is a touch of everyday life in his work that’s instantly familiar. I think in challenging times like we are living through, it’s especially comforting to revisit. I was reading Meditations in an Emergency last summer while creating some of the work in this exhibition.

I chose the poem “The Eyelid Has Its Storms…” as a title because of its evocative imagery. I work a lot with the gaze in my work and wanted to play off of that. I also really wanted to anchor this show to queer predecessors. Frank O’Hara lived a fascinating life and died tragically. So in some way I wanted to honor his legacy.

SL: I always like to ask what other kinds of non-photographic media do you draw inspiration from?

PS: I love sad-ass songs, queer poetry, and good cinema. I also draw inspiration from a lot of my own experiences that I hide in the work.

SL: Beyond the individual collaged works, you’ve made a distinct decision to exhibit many of your works at quite a large scale. I’m curious to hear about how the images change as you blow them up, and your decision to pair or combine and overlay images in the gallery using vinyl on the walls behind the framed works. Can you talk a bit about this and how you see the added layering changing how a viewer interacts with the work?

PS: Scale is a really important factor when working with appropriation. I’ve embraced working larger in the last year as a way to explore color, form, and the materiality of each image. I love the way an image falls apart at a large scale. The printing patterns of the magazines are heightened. It points the viewer to all of the subtle details that I’m interested in highlighting. Combining the framed works with vinyls on the wall is a way of replicating my photographic process in an installation. I like the way I’m able to mimic the metaphor of revealing and concealing a history. The layering of the two becomes another life for the photograph to live, separate from when it’s viewed alone. It’s another way to point to the infinite life of an image and its shifting meaning.

SL: How do you begin a piece? When you know it’s complete?

PS: I usually browse through new material and bookmark images that I think will make interesting juxtapositions. Sometimes I put them away for a couple of years until I find the right thing to do with them. I sort of meditate on an image for a while, then I’ll re-photograph it when I figure out how I want to re-contextualize it. In the past, I would stop myself from trying to “re-work” something after I put it out in the world but recently I’ve been rethinking that. It’s exciting when I’m able to breathe new life into something by making it part of a new diptych or installation. It sort of speaks to the ephemeral nature of the source material.

SL: You’ve mentioned your interest lies in the “slipperiness” of representation and meaning in photography as our culture shifts over time. How do you think we’ll look at your work in the future?

PS: It’s hard to predict the future but I think years from now this work will be a snapshot in time. It will be a marker of where we were in relationship to history. So the context of these images will continue to evolve and become more complicated.

—

Pacifico Silano is a lens-based artist born and living in Brooklyn. He has an MFA in Photography from the School of Visual Arts. His group shows include the Bronx Museum, Museo Universitario del Chopo in Mexico City, Oude Kerk in Amsterdam, and Tacoma Art Museum. His solo shows include Baxter St@CCNY, The Bronx Museum, Fragment Gallery in Moscow, Rubber Factory, and Stellar Projects. Aperture, Artforum, and The New Yorker have reviewed his work. Silano’s awards include the Aaron Siskind Foundation’s Individual Photographer’s Fellowship, Amsterdam’s Pride Photo Awards (First Prize), and the Aperture Foundation Portfolio Prize (finalist). His work is in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Silano participated in Light Work’s Artist-in-Residence Program in 2016.

—

Shane Lavalette is an American photographer and the director of Light Work, a non-profit photography organization in Syracuse, New York. He holds a BFA from Tufts University in partnership with The School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Lavalette has shown his photographs widely, including exhibitions at Aperture Foundation, The Center for Photography at Woodstock, The Carpenter Center for Visual Arts at Harvard University, Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, Fotostiftung Schweiz, the High Museum of Art, Kaunas Gallery, Le Château d’Eau, Montserrat College of Art, Musée de l’Elysée, and Robert Morat Galerie. Many private and public collections also hold his work. Lavalette is the author of four monographs: One Sun, One Shadow (Lavalette, 2016), Still (Noon) (Edition Patrick Frey, 2018), LOST, Syracuse (Kris Graves Projects, 2019), and New Monuments (Libraryman, 2019). One Sun, One Shadow was shortlisted for the Author Book Award 2017 at Les Rencontres d’Arles, nominated for the Kassel Photobook Award 2017, and selected as one of the “Best Books” by photo-eye. Publications and outlets featuring Lavalette’s work include CNN, Foam Magazine, Hotshoe, NPR, The New York Times, The Telegraph, and TIME. His editorial work has accompanied stories in Bloomberg Businessweek, Curbed, Esquire, Monocle, The Guardian,The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, The Wire, Topic, Vice Magazine, and Wallpaper. Lavalette is represented by Robert Morat Galerie in Berlin and We Folk agency in London and New York.