“What is She Doing There?”: Susan Lipper on Kristine Potter

The Light Work blog is excited to present this reflection by Susan Lipper, recent Guggenheim Fellow and 2004 Light Work Artist-in-Residence, on the work of Kristine Potter, 2014 Light Work Artist-in-Resident. Both graduates of the Yale Photography MFA program and women photographers working out West, it is a unique pleasure to read Lipper’s words on Potter’s images.

—

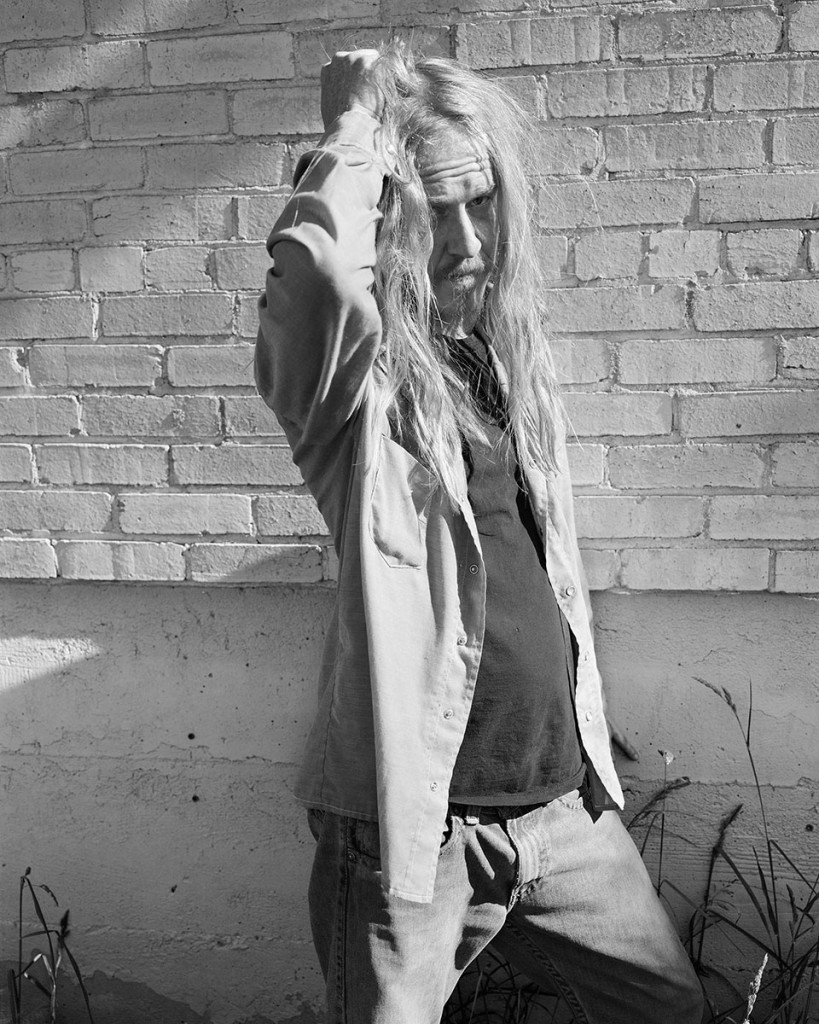

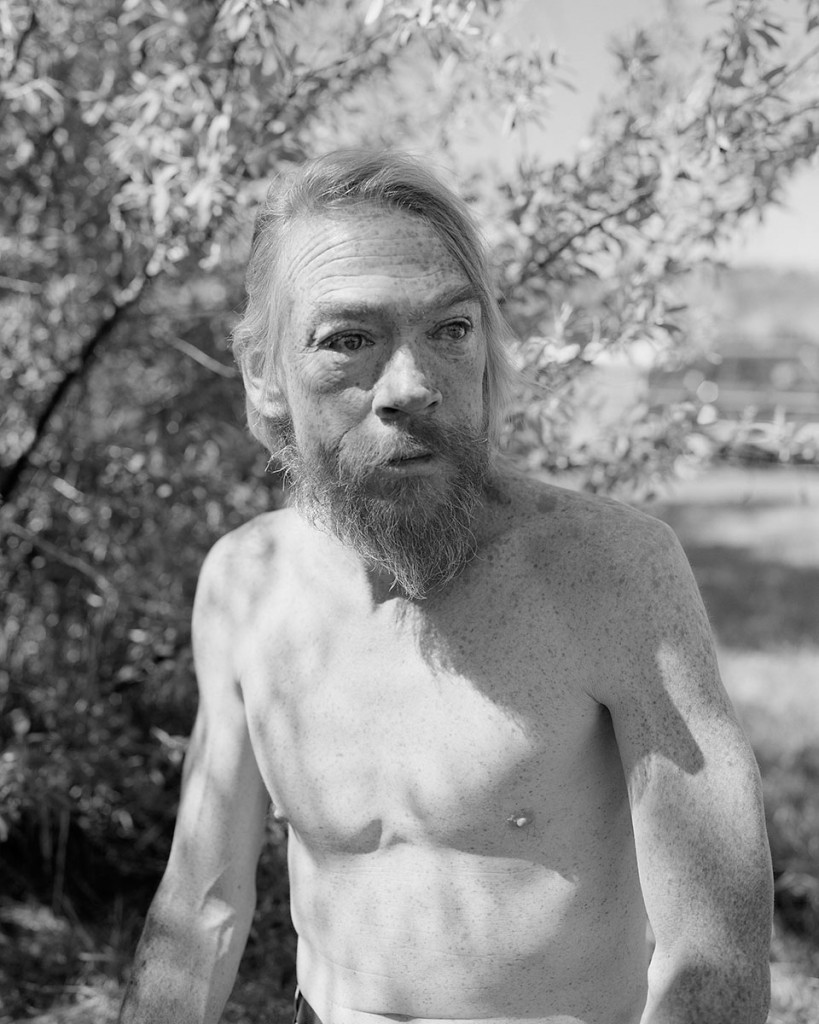

In thinking about Kristine Potter’s fascinating Manifest series, Gertrude Stein’s off-quoted phrase “there is no there there” came to mind: that beyond our looking at these exquisitely crafted images, taken over three years on the Western Slope of Colorado, both portraits and landscapes, we are also looking at a fantasy of a fantasy.

The artist has undertaken to flip some of our most persistent cultural tropes: America, a woman alone on the road, the West, wilderness, and the state of man in nature. She has also consciously deployed a motif (dear to me) of the subjective documentary approach, where beyond that being depicted, we are also expected to consider the identity of the photographer. At the very least, it seems integral to the reading of this work to know the photographer is a woman. (Even if we weren’t told the gender of the photographer, these images of men don’t look like the work of a peer’s or at least someone they have no romantic interest in, as evidenced by many of their telling gazes.)

In addition, this work is interesting because as a woman and photographer, I cannot help but question the imagined personal risk involved in manufacturing these works with all the necessary transaction involved with sitters both pre- and post-portrait session. (In general though the perceived effort behind the making of an image does not sway me.) In reviews of this work I’ve read written by men, this topic is not broached. Perhaps I am reading too much, but the question constantly returns: “What is she doing there?” Why this ongoing playing with chance that the shooting of a portrait in presumed isolated locations with strangers (who are mostly unaware of the art context and perhaps confused by the initial invitation to be photographed) will go as planned and negotiated? This is not to say that the risk taking isn’t completely admirable.

Then, finally, who are these pictures for? Who is the intended audience? Not that it matters because the work is formally rich enough to transcend such divisions. However, I feel we are looking at more than an August Sander–esque documentary series of the Western male archetypes at a particular point in time; we are also looking at a double-sided portrait, containing both an investigation and a projection, where we imagine the self-image of the photographer as some kind of solitary huntress–perhaps lion tamer–and evidence and celebration of a new brand of feminism.

As we follow the artist’s journeys from the “cultivated” East to “wild” West from the cadets of West Point in her 2010 The Gray Line series, to the different uniformed personas of the cowboy and loner in Manifest, we sense an increased risk of personal danger due to these new uncharted and semi-lawless subjects. Her journey perhaps mirrors the once-cherished Manifest Destiny myth where personal heroics ensured our American right to prevail.

More to the point, I suspect that the photographer, like many of us steeped in the evolving face of patriarchy, is rethinking that grand nostalgic notion. Accordingly the Manifest series intentionally and necessarily aims to record the changing reality versus the well-trodden mythology of the West. Perhaps this is where the truncated but still beautiful landscapes come into play–not that I doubt that Romantic nineteenth-century vistas were also plentiful.

In any case the men depicted here, despite their rugged individuality, do not seem up to the task of discovering/rescuing America. Further, it appears that even our distinct concept of America as an isolated country is fading. How is the country to be seen as actually quarantined from the rest of humanity forced to heed the prevailing forces of global economics and capitalism? So much of the previous search for heroes seems like closing the stable door after the horse has left. Realistically our hopes should probably no longer be with the individual, no matter how much he is like the film character Crocodile Dundee, victorious both in the Outback as well as among the powered elite.

Winter Landscape (spots) from Manifest, 2014

Potter has assembled her male subjects almost as if they were reverse film noir character heroes bathed in western light. However, while they are empathically portrayed, their personal space is intentionally constrained and mostly there is nowhere for them, the artist or viewer to go, which is both symbolic and a breeding ground for confrontation. Admirably these men wish to retain their otherness and resist being commoditized. This friction endows each portrait with an electric charge. So much so that in one of her almost set-like shallow landscapes, Winter Landscape (spots), 2014, I persist in reading the trace of a bullet hole piercing “the surface” of dense vegetation.

—

Susan Lipper is a New York based artist. She received her B.A. in English Literature from Skidmore College in 1975 and her MFA in Photography from Yale University in 1983. Among the monographs on her work are Bed and Breakfast, 2000; trip, 1999; and GRAPEVINE, 1994. Lipper is represented, amongst other places, in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. She is the recipient of numerous awards, including fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, New York Foundation for the Arts, and the 2015 Guggenheim Fellowship. She was a 2004 Artist-in-Residence at Light Work. She is currently working on an ongoing project in the California desert as the final chapter in a trilogy of her travels from East to West.

Kristine Potter was born in Dallas, Texas and lives and works in New York City. She earned both a BFA in Photography and a BA in Art History at the University of Georgia in 2000. From 2000 – 2003 Kristine lived and worked as a professional printer in Paris, France. In 2005 she earned her MFA in Photography from Yale University. Potter’s work has been exhibited in Paris, New York City, Miami, Atlanta and Raleigh, NC. Her work is in numerous private and public collections, including the Georgia Museum of Art, and has been recently featured on Hyperallergic.com, HAFNY.org, among others. She is represented by Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York City, where she exhibited her 2015 solo show, Manifest.