On Being “The Photographer’s Wife,” an Interview With Laura Heyman

Laura Heyman and Jessica Posner

Laura Heyman is a photographer, Light Work Lab member, and Associate Professor of Photography in the Department of Transmedia at Syracuse University. She’s been working in the Light Work Lab in recent months in preparation for her current exhibition, Render, at Artspace in Raleigh, North Carolina. The exhibition features a collection of images from Heyman’s ongoing project, The Photographer’s Wife; and is on view from Sept. 2- Nov. 5. 2014. Below, Jessica Posner (Light Work Communications Coordinator) interviews Heyman about her work, process, subjectivity, humor, and more.

—

Jessica Posner: You’ve been in the Light Work Lab a lot in recent weeks preparing for an exhibition. Can you tell us a little about the project you’ve been working on?

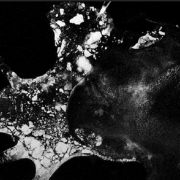

Laura Heyman: I’ve been printing images from The Photographer’s Wife, a project I began in 2003. The photographs present a female character as the central subject, often gazing intimately at the camera, suggesting an artist making images of their lover. The locations in the photographs vary, but many of them are domestic interiors, further adding to the feeling of intimacy – viewers get the sense they’re seeing something which is essentially private.

Untitled from The Photographer’s Wife, 2006

JP: In these images, you are both subject and object; but not in the sense of a traditional self-portrait. You are mediated by a fictional character. Can you talk about how you play with the position of the subject/object in this body of work?

LH: The model/subject’s job is always performative — she must be able to portray both a true and idealized self. But in the case of these photographs, the problem is slightly more complicated. As the model/subject, I must convey not only this multiple subjectivity, but also reflect back to the viewer an imagined photographer husband.

JP: Would you care to go a little deeper into one of the images (your choice)?

LH: There’s an image I made in the bathroom of an apartment in Florence this summer. The location had a really strong pull for me – it’s a beautiful room, with amazing light that’s also kind of harsh. There’s a strong color scheme, and the space is a little strange, because the bathtub looks like it was made for a small child.

Untitled from The Photographer’s Wife, 2014

I knew I wanted to make an image in the room, but wasn’t sure what exactly what to do with it. A week before returning to the States, I found a color photograph from a 1940’s magazine showing a woman sitting in a very similar bathtub. She had her back to the camera and was looking into a small hand mirror, hair piled on top of her head in a bun. As soon as I saw the image, I knew that was it.

I began imagining the conversation/negotiation between the artist and model that could have brought them to that pose, and other iterations they might have tried but ruled out. I spent a couple of days looking for an appropriate hand mirror, observed the light in the room over another couple of days, and at the appointed hour, set up the shot. I filled the tub with water, approximating the pose from the magazine over two rolls of film, stepping in and out of the tub to set the self-timer and wipe the water off the floor in between shots. On the third roll of film, I changed the pose, leaning back against the wall to face the camera. I’d been up late the night before and it shows – the light in the room accentuates the circles under my eyes and every crease on my body. It’s a strange picture. When I saw the contact sheets I almost didn’t recognize myself. There were only a few of the non-mirror images from the shoot, but these are the ones I was most drawn to, and what I ended up using for the exhibition.

JP: Can you give us a little insight into your working process? Both conceptual and technical?

LH: On the technical side, I’m usually shooting medium or large format film. Up until a few years ago, this was true of both still and moving images – I shot 16mm film rather than video. Now I shoot mostly analogue large format film and video.

Conceptually some projects are very simple – there’s something happening that I feel should be recorded. This was the case of The Last Party, which documented the final days of Ocho Loco, a warehouse I occupied in San Francisco from 1990 – 2003. In 2003 the building was slated for demolition (to make way for live/work lofts). My roommates and I wanted to do something to commemorate the space before it disappeared. So every band that had ever played there was invited back for one last show, which lasted almost 24 hours. I drank a lot of coffee and photographed the party from beginning to end.

Bagdon (Left) and Maggie (Right) from The Last Party , 2003

With other projects, the process is a little more complicated – it may start with a question, something I’ve been turning over in my head for a while. The Photographer’s Wife was partially influenced by a story a friend told me about the wife of a well-known photographer in San Francisco. In college, I’d seen the requisite images of Eleanor Callahan, Edith Gowan and Bebe Nixon that were part of any photography student’s education, and I had always been fascinated by them. I wondered about their lives, wondered what they thought about the images we’re all so familiar with. Then I received this sort of inside story detailing what it was like to be a strong intelligent woman involved in the creative process in a very direct way, but without any of the rewards that artists normally expect or receive. I realized these women weren’t the romantic figures I had imagined them to be when I was younger, but they weren’t tragic or exploited either. I had been making some images of myself, not self-portraits, more like performance stills, and hearing this story made me see those images in a new light, moving the work in a very different direction. I began thinking about and researching performance, reading biographies of artists, and looking at a lot of work that explored questions similar to the ones this research produced for me.

JP: Is there a thread that flows through all of your work? What is it? Where do you think it comes from? How do you see it manifest in this body of work?

LH: I don’t know if I could say there’s a thread that runs through all of my work. It tends to change a great deal from project to project. But there are definitely themes I return to; one is an interest in narrative structure, and the ways that narrative can be transmitted to the viewer. The narrative form that drives a lot of my research is cinematic, in part because film has the ability to colonize human experience and memory in ways that are almost impossible to quantify. So some of my work borrows from cinema’s use of art direction, set design and location. The second constant in my work is performance, which is of course inherent to the medium of photography; any subject who stands before the camera is arranging and editing not just their appearance, but also their persona. But I’m concerned with the performance taking place on both sides of the camera, how power can shift between photographer and subject, whether the image resulting from this exchange is more a representation of one or the other, and to what degree.

Untitled from The Photographer’s Wife, 2009

Part of this interest comes simply from being a female artist who, as a student, learned about art by looking at images of women created by men. I’ve always been interested in the lessons art history teaches women, specifically those regarding the female muse. I wonder if it’s possible to internalize these lessons, and if so, what effect does this have on one’s own production?

This question became really significant to The Photographer’s Wife, alongside the question of whom I was performing for when I stood in front of the camera. In performing for this imagined figure (behind the camera, operating the camera), I began to think about who that might be and how to conceptually occupy both of those spaces and perform both of those idealized roles at the same time.

JP: Does humor play a role in any of this current body of work?

LH: I think so, but maybe I have a strange sense of humor. I find the performance of frustration or exasperation that occurs at certain points in the work very funny. Likewise, moments where the attempt to portray a feminine ideal is problematized or falls short, where the model is not seen at her physical best, but projects awkwardness and exhaustion instead of the expected languor and appealing, flirtatious sexuality – people often laugh when they’re uncomfortable, and for me these images are like a joke the viewer isn’t sure they should be laughing at.

Untitled from The Photographer’s Wife, 2007

JP: I recently had the opportunity to meet your son Ace, age 10, who told me that looking at a photograph is like looking at a past life version of himself. It made me wonder what life is like in your house. What books do you have lying around? On your bedside table? On the coffee table?

LH: We’re big readers, so there are books all over the house. Most photo books live in my office but there are a few at home, among them The Wedding by Nick Waplington, which has been a favorite of Ace’s since he was baby. On my bedside table at the moment are A Visit From The Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan, Changing My Mind, by Zadie Smith, The Testament Of Mary by Colm Tóibín, and My Teachings by Jaques Lacan. Although I have to confess that last one was purchased at the end of the summer when I was feeling particularly relaxed and ambitious – I have yet to crack the spine.

JP: What are you working on now/next?

LH: For the past several years I’ve been working on two long term projects – The Photographer’s Wife, and Pa Bouje Anko: Don’t Move Again, both of which are pretty intense. So I’ve been researching ideas for something different, and this summer started collaborating with an artist named Michel LaFleur, who’s based in Port-au-Prince. The project is just beginning, so it’s pretty loose at this point, but the main ideas are based around language; the power and play of language and the written word. Michel is a sign painter, and we’re working with lists, titles and translation, producing videos and a series of small paintings. It’s been great to work with another artist, and in another medium.

JP: Details about the exhibition?

LH: The exhibition was the start of a season-long examination of the use of the figure in contemporary art. Curator Shana Dumont Garr wanted “to explore the iconic relationship between the depicted and the depictor…. the ways that staging and self-consciousness may affect viewing experiences.”

Exhibition Details:

Render: Laura Heyman and Leah Colie Wight

September 5– November 2, 2014

Artspace

Raleigh, North Carolina

Untitled from The Photographer’s Wife, 2005

Laura Heyman was born in Essex County, New Jersey and received her M.F.A. from Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, MI.Solo exhibitions include Palitz Gallery, NY, NY, Silver Eye Center for Photography, Pittsburgh PA, Philadelphia Photographic Arts Center, Philadelphia, PA, Deutsches Polen Institute, Darmstadt, DE, Senko Studio, Viborg DK, and Light Work, Syracuse, NY. Group exhibitions include Laguna Art Museum, Laguna, CA, United Nations, New York, NY and National Portrait Gallery, London, UK. Heyman has received grants and fellowships from Light Work, The Silver Eye Center For Photography, Ragdale and NYFA, and her work has been reviewed and profiled in The New Yorker, Contact Sheet, and ARTnews. Heyman is an Associate Professor of photography in the Department of Transmedia at Syracuse University.

Jessica Posner is an artist, Communications Coordinator at Light Work, and Adjunct Faculty in the Department of Transmedia at Syracuse University. You can contact her at jessica@lightwork.org.