Re:Collection: Sydney Ellison on Pedro Isztin

Visitors to Light Work’s website are invited to explore thousands of photographic works and objects from the Light Work Collection in our online database that expands access of work by former Light Work artists to students, researchers, and online visitors. Our Re:Collection blog series invites artists and respected thinkers in the field to select a single image or object from the archive and offer a reflection as to its historical, technical, or personal significance.

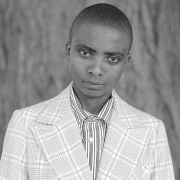

Today we’re sharing a reflection on Pedro Isztin’s image Stan, 2009 from Sydney Ellison. Ellison is a Brooklyn-based artist whose work addresses themes of gaze and intersectionality primarily through collage and self-portraiture. Ellison is an art photography student at Pratt Institute and an editor of The Photographer’s Greenbook, a resource hub for inclusion, diversity, equity, and advocacy in the lens-based art community.

—

When searching through Light Work’s collection, I was immediately taken aback upon finding Pedro Isztin’s Stan (2004). In this image, almost all the space inside the frame is taken up by the face of an elderly man with bloodshot, blue eyes, a stern gaze, and a small black and white photograph secured on his forehead with red tape. I was taken aback by how confrontational this image is when I first saw it, but the more time I spent with it the more complicated it became. I am not aware of the original context of this photograph, but something about the tension between the deep blues and bright red and the presence of another photograph within the photographic frame feels like a piecing together of contexts. While the tightness of the frame and the direct gaze of the subject are obviously confrontational, his expression seems to be more one of pleading than of aggression. It is this pleading expression and the photograph taped on his forehead that made me think that the nature of photography itself is the subject of this photograph. It is nostalgic, it fixes a moment in time, and it fails to live up to reality.

The positioning on the man’s head of the photo of a baby, whose gaze is similar indirectness to the subject’s, seems to illustrate memory and the idea of a photograph as an object that houses a memory. The man’s age seems to reference loss. While this could be memory loss it could also simply be the loss of who one used to be and what they once had. This caused me to wonder, are photographs where we store past versions of ourselves? I think that often they are. Because of this, the reckoning with a photograph, presumably from another time, within this image is largely what makes it so enchanting and unnerving.

Internships at Light Work

Offered year-round, Light Work internships provide a platform for undergraduate and graduate students to gain practical, hands-on experience in our exhibitions, education, and collections departments. Light Work’s programming includes exhibitions, educational classes, workshops, community education programs and initiatives, residencies, publications, a digital darkroom, and a library. We endeavor to match each intern with duties that match their interests and learning goals. To apply for internships fill out our Internship Application PDF and send it and all requested documents to lab@lightwork.org