Visitors to our website are invited to explore thousands of photographic works and objects from the Light Work Collection in our online database that expands access of work by former Light Work artists to students, researchers, and online visitors. To coincide with the our collection website launch, we’re introducing a series on our blog called Re:Collection, inviting artists and respected thinkers in the field to select a single image or object from the archive and offer a reflection as to its historical, technical, or personal significance.

Today we’re sharing a reflection on Gerald Cyrus’ Untitled (from the Kinship series), New Orleans, LA, 1991 and Untitled (from the Kinship series), New Orleans, LA., 1993 from 2018 Light Work artist-in-residence, Aaron Turner.

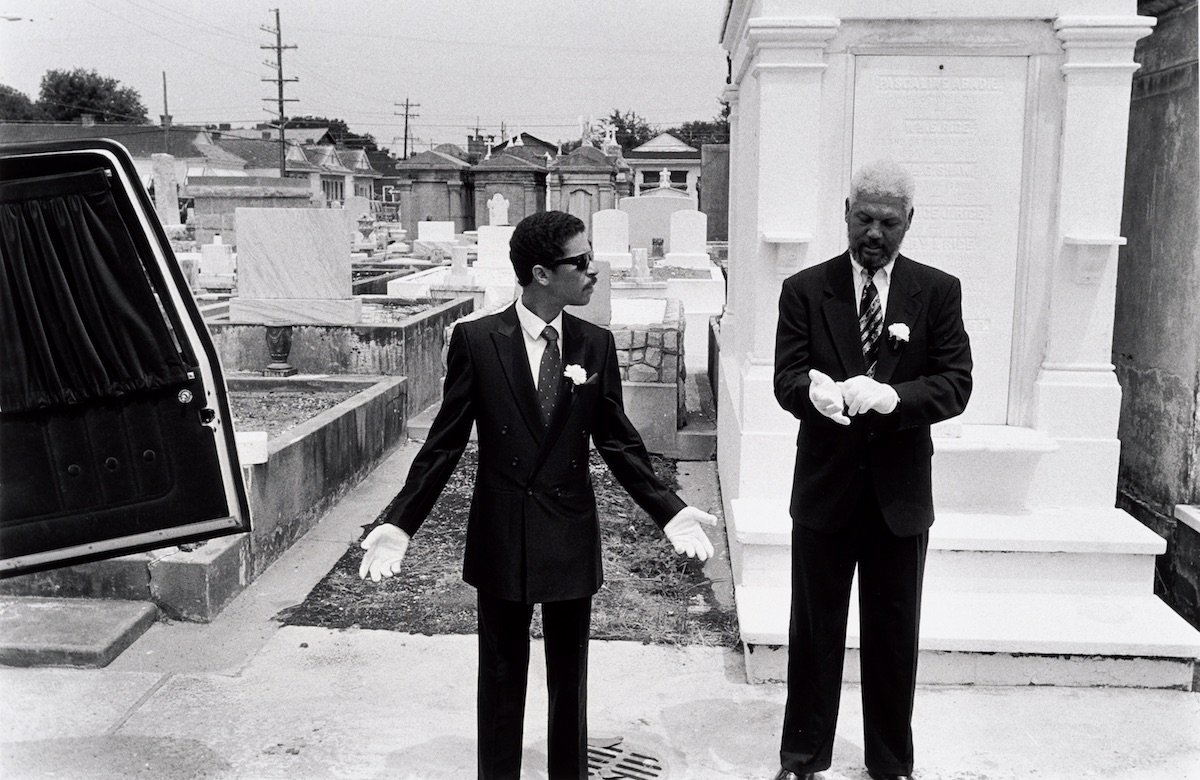

Coming across Gerald Cyrus’ work in the Light Work Collection, I was immediately drawn to a photograph taken in a graveyard, seemingly after a funeral or sometime during the burial. Having made photographs at several funerals myself, three this year alone, I find the funeral, yet sad, is almost a place of peace. For me, a portion of funerals resembles a family reunion, and I am glad to see my family, not under the perfect circumstances most certainly, but the rituals of the ceremony and voices of the young and older relatives bring a sense of comfort that there is more to be passed down. A life is lost, but in reverence, many lives come together to share a collective expression of grief.

The two gentlemen in the photograph have taken pride in the duty they’ve been tasked. Are they pallbearers, representatives from the funeral home? An essential part of our society, funeral homes are a cornerstone in the black community, from my perspective. This is especially so in photography, if we reflect on the work of photographers such as Latoya Ruby Frazier, Henry Clay Anderson, James Vander Zee, Moneta Sleet Jr.

We can add various emotions, layers, feelings, thoughts to a photograph after the fact, many of which the photographer never intended or considered as the individual who recorded that moment. That’s what I feel when I look at Gerald Cyrus’ photograph with several of his family members holding cameras, photographing something out of frame. Looks like a family event, a birthday, a wedding, perhaps after graduation?

This image reinforces so many of the internal considerations that I begin to project on to it my experiences as a black man and photographer. The individuals are legitimate stand-ins for my family members. In this image you see five family members holding cameras, four of whom are black women. This alone evokes many things in the history of photography. Makes me think of the influence Carrie Mae Weems’ work had on Mickalene Thomas, who said she never knew black women made images until seeing Weems’ work.

And considering Cyrus himself recording this moment, etching it into this permanent existence—furthermore, examining the historical implications of this photograph—in this moment we realize that we can and have been recording our own stories as black people.

What I like most about these two photographs by Cyrus is that he’s taken the time to consider family through photography. Another critical element of the pictures is time: I mean this not in the sense of a decisive moment, but in the implication of representation and the proximity of an individual’s family histories to the overall narratives of America, art history, and indeed the world. He made both images in the early 90s, when I was a toddler, but here I am in 2019, following the footsteps of Cyrus and countless other photographers, documenting my family, in many of the exact same situations.

Find more of Aaron Turner’s work online here.

Explore the Light Work Collection online at http://collection.lightwork.org