Rachelle Mozman on Costa del Estes

Rachelle Mozman’s exhibition Costa del Estes is currently on view at Aguilar Library in New York City until April 2, 2011. Rachelle and I recently talked about Costa and her other work in an email interview that traverses the suburbs of New Jersey and Panama, the politics of being a child in different cultures, and Mozman’s latest images of her mother.

Mary Goodwin: Earlier this month, you opened a show of your work Costa del Estes at the Aguilar Library as part of En Foco’s Touring Gallery Exhibition series. Costa del Estes, as well as a parallel series called American Exurbia, have been developed over the past couple of years. These bodies of work imagine the life of children in gated communities in Central America and the United States, settings that you describe as “. . . isolated, secure, and homogenous.” How did you get interested in making work about these communities?

Rachelle Mozman: I was initially interested in photographing what I saw to be the changing landscape of areas now known as exurbia in New Jersey. I had been driving out to teach at a community college in Randolph New Jersey, and I simply started noticing all the new corporate campuses and gated communities going up where woods once were. I was very attracted to photographing the changes. I started out making photographs of security guards in front of their posts, but then was drawn to the women I would see and then introduce myself to in the Dunkin Donuts. Then, gradually, through photographing the women in their homes, I became very interested in photographing their children. Once I began making photographs of the children, there was something that was coming through in the pictures that was very emotional for me, and I found myself narrowing in and just focusing on the children. I had grown up partially in the suburbs of New Jersey as a teenager, and I always felt a profound isolation in the American suburbs. When I realized that exurbia and the gated community was taking the idea of the suburb to a new level of isolation and homogeneity of class, I was really drawn to exploring this, and the fantasy of isolation in order to achieve safety from the city and the other.

When I traveled to Panama in 2005 and realized that the gated community phenomenon had moved down there, I felt I had to make photographs. Costa del Este is the name of this gated community, where in essence all the middle class and wealthy Panamanians have moved to in the last five years. Each neighborhood has a gate, and they have a separate school, mall, etc. I was fascinated by the imitation of American lifestyle, but in a very Latin American, Panamanian way. Children there are brought up in a very small bubble, again from fear of interacting with another class or race, and fear of crime. But incidentally as the wealth and separation of class grows, so does the crime.

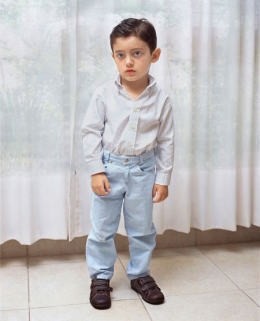

MG: There’s a curious power dynamic going on in Costa. All of the subjects are quite young, with the oldest looking not even tween. However, the helplessness and dependency associated with being that young is equalized in a couple of ways. Firstly, the camera is always at the children’s level giving their gaze as much importance as the viewers’. Secondly, the children don’t act like children — the way they stand and gesture has an oddly adult character to it. Do the children somehow reference the adults who also presumably populate these interiors?

RM: Yes, absolutely, the children in Costa do reference the adults. It could also be due to how they are taught to interact in front of a camera, as well as my interest in representing who they might be when they are adults. I believe the power dynamic that is picked up on in the photographs is based on the children’s sense of self-identity as an adult might have. It’s an identity that is tied to a sense of entitlement. Because the children rarely interact with people they don’t know (they are primarily in a small circle of their family and their maids), I often felt while photographing that they saw me as hired help. This is partly why there is that sense of power in their pose, and also why I chose to place the camera at eye level. I was drawn to revealing this and their conditioning. But after a few years I became very saddened by it.

MG: How have the children reacted to seeing themselves in your images?

RM: They often feel that the photographs are beautiful, but because they are not being represented in a way they are accustomed to seeing in the local socialite magazines, hair being fluffed, and heads tilted to one side, the pictures don’t appeal to them enough. They also do not see these photographs as art, more as snapshots of people they know. As a consequence they would never buy one and place it in their homes, because it would be a snapshot of some one else’s child.

MG: Who have you been looking at as you’ve developed this series? Which artists have influenced your work along the way?

RM: Roger Ballen is an influence. Also the work of August Sander is an influence, as well as the painter Velasquez and other portrait painters of the 16th and 17th century. I was thinking a lot about the strangeness of some of Sander’s portraits as well as the representation of identity and power in the paintings of Velasquez. I am often told my pictures are strange, but it’s not something I intentionally aim for. I feel that Sander was not trying to make strange images either, but sometimes something is revealed there. This tension is something that I am interested in.

MG: Tell us a little about your participation with En Foco. How have they supported you as an artist, and specifically this exhibition? What is their Touring Gallery Exhibition series — will Costa tour to multiple venues?

RM: En Foco has been wonderful, and I am very happy that they invited me to exhibit. They are a very important institution, and they do wonderful work. I love the idea of placing this work outside the context of the art world into the community. There are no immediate plans as of yet to continue touring the exhibit, but I would be happy to do it!

MG: While you were a Light Work Artist-in-Residence, you worked on printing images from Costa and Exurbia and also on shooting images for the series that eventually became Scout Promise. Can you explain what the Girl Scout Promise is for those who weren’t Scouts themselves earlier in life? Promise seems to be connected to your earlier series through the idea of exclusive communities/groups that impose an artificial order on childhood. Although in Promise, the children seem to have a healthier, more connected relationship with the environment?

RM: Yes, I am really interested in exploring that “artificial order” on childhood you mention. But I think it’s my interest in how societies are structured and how children are conditioned that is at the heart of my interest in photographing childhood. In Girl Scout culture the promise is at the center of what they teach the girls. I found it to be simultaneously beautiful and terrifying that the girls would recite this promise at the start of every meeting.

It’s the same attraction and terror I feel toward any structured group. In general I find the Girl Scouts to be very positive and even essential for girls, particularly in third world countries. I photographed the girl scouts in Panama, and I found it to be so important. In countries where the feminist movement has not gained strength, or where women have fewer rights, I feel that the Girl Scouts offer a great support and outlook for the girls. Who else in a predominantly Catholic country will teach them about sex education and the importance of protection against sexually transmitted disease?

MG: Most recently, you’ve started making pictures of your mother. Please tell us about this most recent series.

RM: The photographs of my mother are more overtly performative and theatrical than my previous work, although one can tell in my prior portraits that I am interested in blending the document with the narrative. The work with my mother, entitled Casa de Mujeres, represents three characters that are all played by my mother: an upper class woman, her darker twin sister, and her maid.

To make these images I borrowed heavily from stories from within my own Panamanian family. But the images represent a fictional home in a fictional Latin American country. In fact, so far I have photographed within the colonial homes of three Central American countries to make these images. The pictures address the conflict of race and class that can exist under one roof within Latin America, as well as within one person. Ultimately these photographs can be read as portraits of my mother as her various selves—like a nested doll—and read as images that reveal the conflict of vanity, race, and class that live within one woman.

MG: Costa del Este will be at the Library until April 2. What’s next in terms of exhibitions and publications? Where can we look for your work in 2011?

RM: In March I will be exhibiting in the launch of Humble Arts Foundation book launch of Collectors Guide Vol. 2. In June I will be exhibiting in the S Files Biennial at El Museo del Barrio, and later in the year I will be exhibiting in a commissioned project for Foto España.

MG: Thanks for catching us up on your work, Rachelle.

Images (from top): Cost Azul, 2006; Twins in Yellow, 2007; Group of four with rope, 2009; En el cuarto de la niña, 2010.

Dear Rachelle,

I really love your work.

Beautiful, realistic and poetic.

Congratulations,

Maria Luiza.

Thanks for the insight into this beautiful work.