Anouk Kruithof Talks Books, Travel, Feminism & More

Anouk Kruithof is a Dutch artist currently based in New York City. She has been exploring and questioning the picture-plane, image, materiality, physicality and philosophy of the medium of photography for over a decade. Her multi-layered, interdisciplinary projects take the form of photographs, installations, artist books, text, sculpture, ephemera and performance. Kruithof was an Artist-in-Residence at Light Work in May 2013. Her new book, The Bungalow, was recently published by Onomatopee. She recently launched a Kickstarter campaign for her forthcoming book, AUTOMAGIC, which she worked on while in residence at Light Work.

Below, Kruithof and Light Work’s Jessica Posner engage in a conversation about The Bungalow, AUTOMAGIC, travel, feminism, and more.

—

Jessica Posner: Hello, Anouk! You were an Artist-in-Residence at Light Work in May 2013. Can you tell us a bit about what you worked on during that time, and what you have been up to since then?

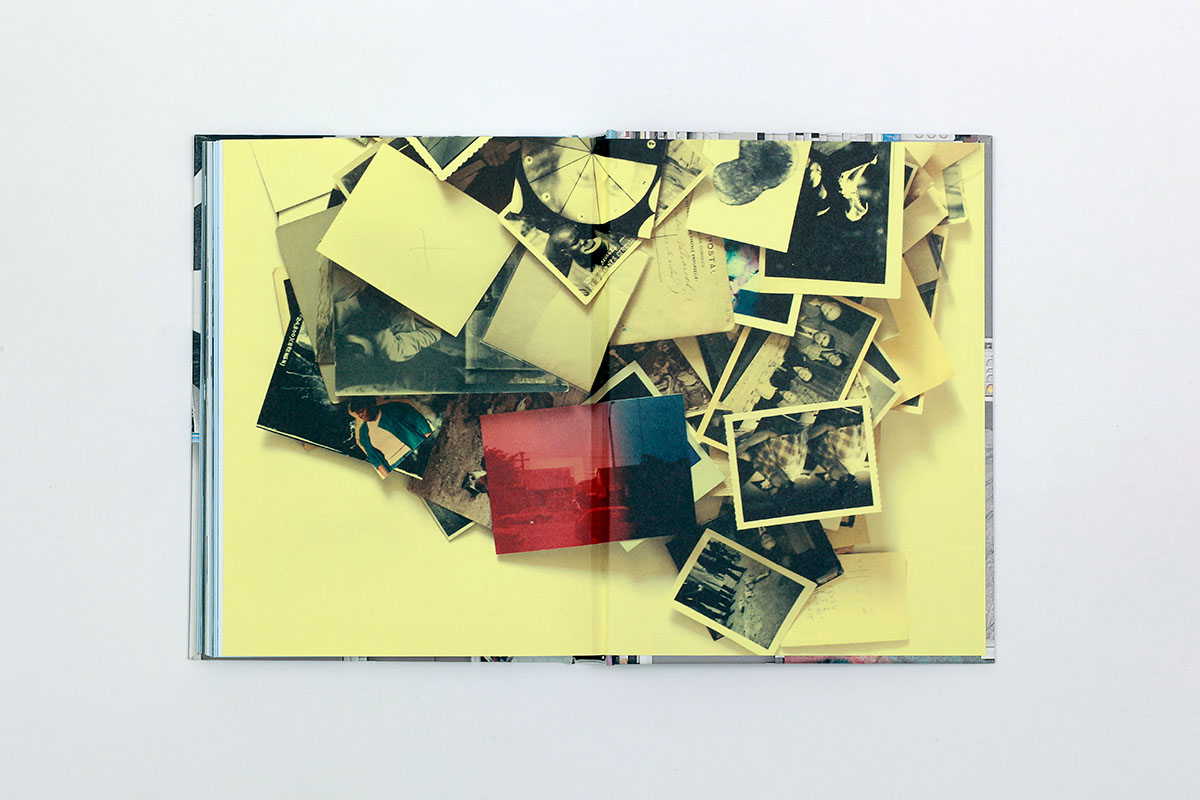

Anouk Kruithof: During my Light Work residency, I spent the first week on my book Pixel Stress, which was published by RVB Books in September 2013. The other weeks I worked on my upcoming book, AUTOMAGIC. It is a very extensive project containing work from 2003 through 2015, which I started working on in May 2011. Readers can check out my Kickstarter to learn more about AUTOMAGIC.

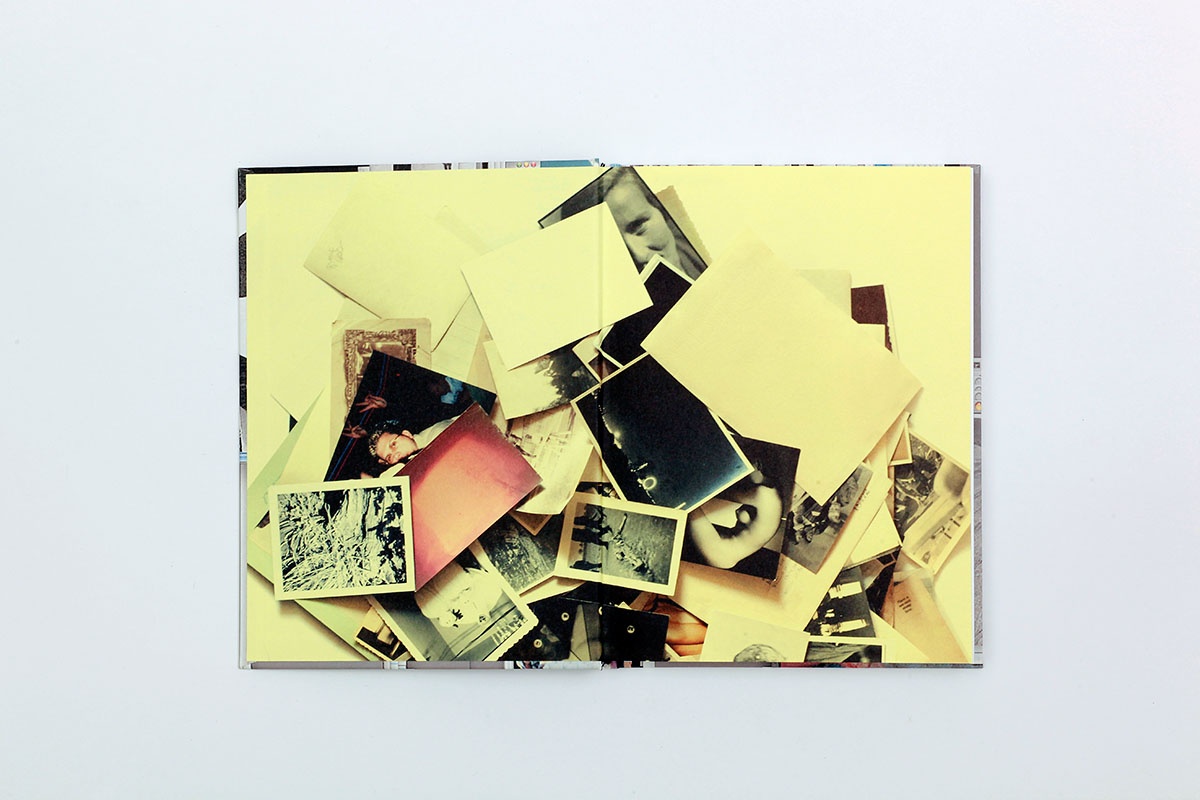

In 2013, I made the solo show Everything is Wave in gallery Boetzelaer|Nispen in Amsterdam, Netherlands. In the Spring, my small solo exhibition Within Interpretations of a Wall opened at Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. I did nine months as an artist-in-residence through ISCP in New York. This summer, I started my publishing platform, Stresspress.biz. I’ve published two more books: Untitled (I’ve taken too many photos / I’ve never taken a photo), self-published, and The Bungalow, published by Onomatopee. Shane Lavalette, the Director of Light Work, basically checked the first dummy of The Bungalow in May of 2013.

In the past year I’ve traveled a lot too: Jamaica, Mexico, LA, and Europe. I’m currently living in New York City, and I just found a new studio on the Lower East Side. I am crazy about it!

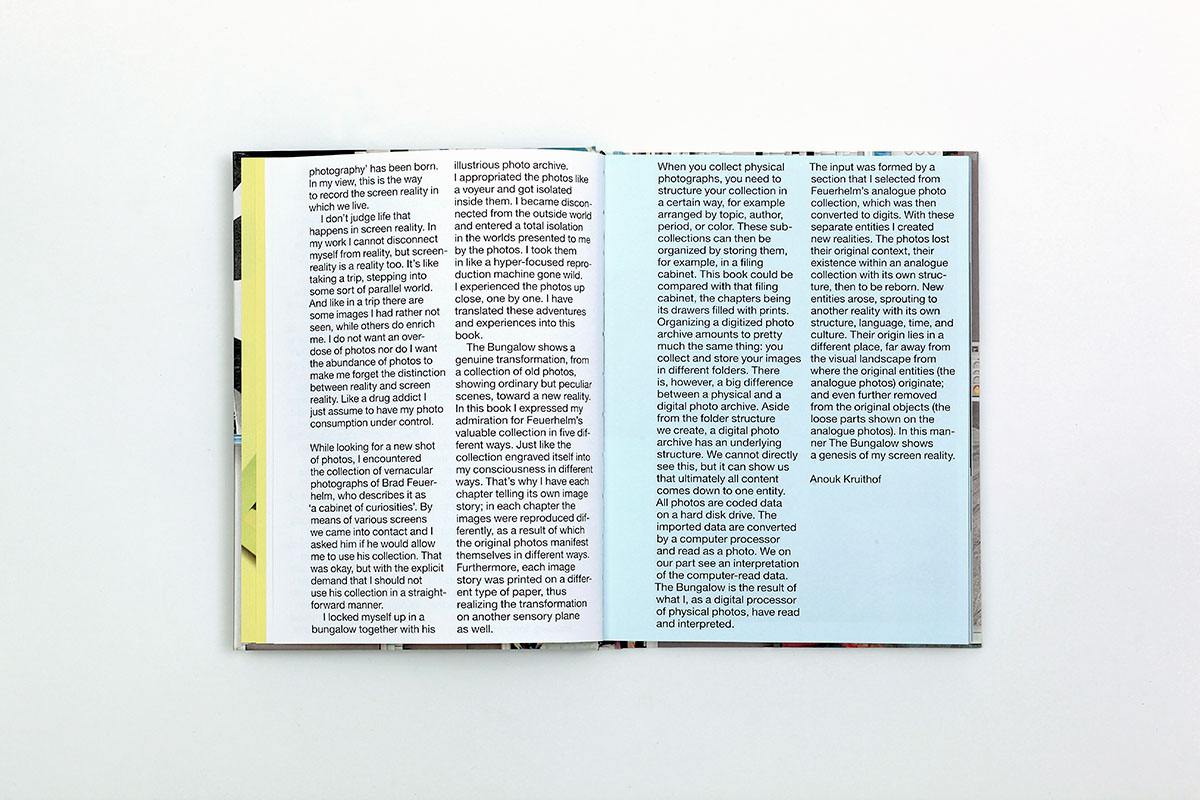

JP: It sounds like you’ve had an amazing two years. Congratulations! I’d like to start off a conversation about The Bungalow by asking you about a phrase that you use in the introduction of the book, “screen-reality.” Can you expand on that term?

AK: The world by now is dominated by photos. In this world, people function as processors of an ongoing stream of images. For many of us, it has become more normal to look at the world through a computer or iPhone screen, than seeing it in physical reality. We filter reality by means of a screen, and thus experience life in this way. That reality is limited to a rectangle, even though this screen-reality is ascribed a “full view.” But the real full view, the context, fades when we take in such large quantities of photos through a screen. Photos have become pieces of evidence of entities. By this I mean that a thing that has been recorded only exists because the photo shows us it’s there. For many, a photo is proof that what is depicted exists for real, even without physically or consciously having seen the object in reality. Seeing in the physical sense has been degraded because of this. Seeing is the only sensory process remaining, while the other sensory experiences—smelling, touching, tasting and hearing—have no role to play in screen-reality.

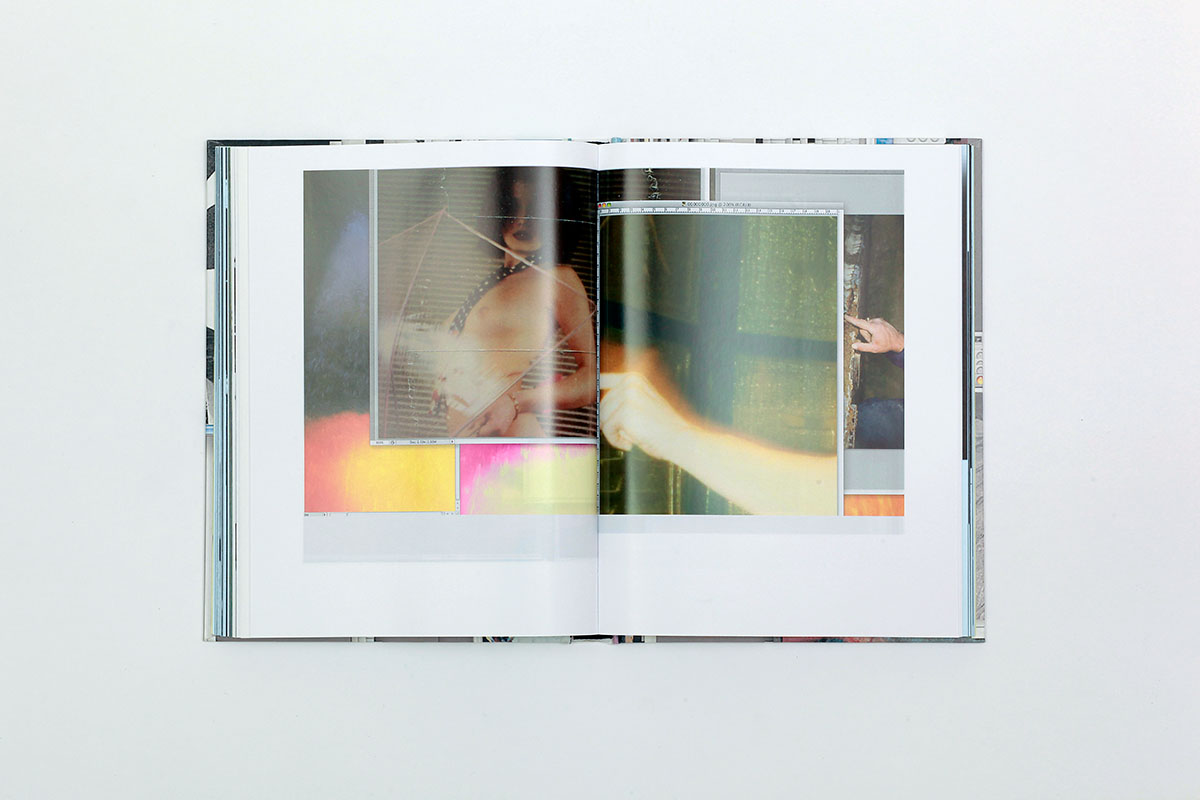

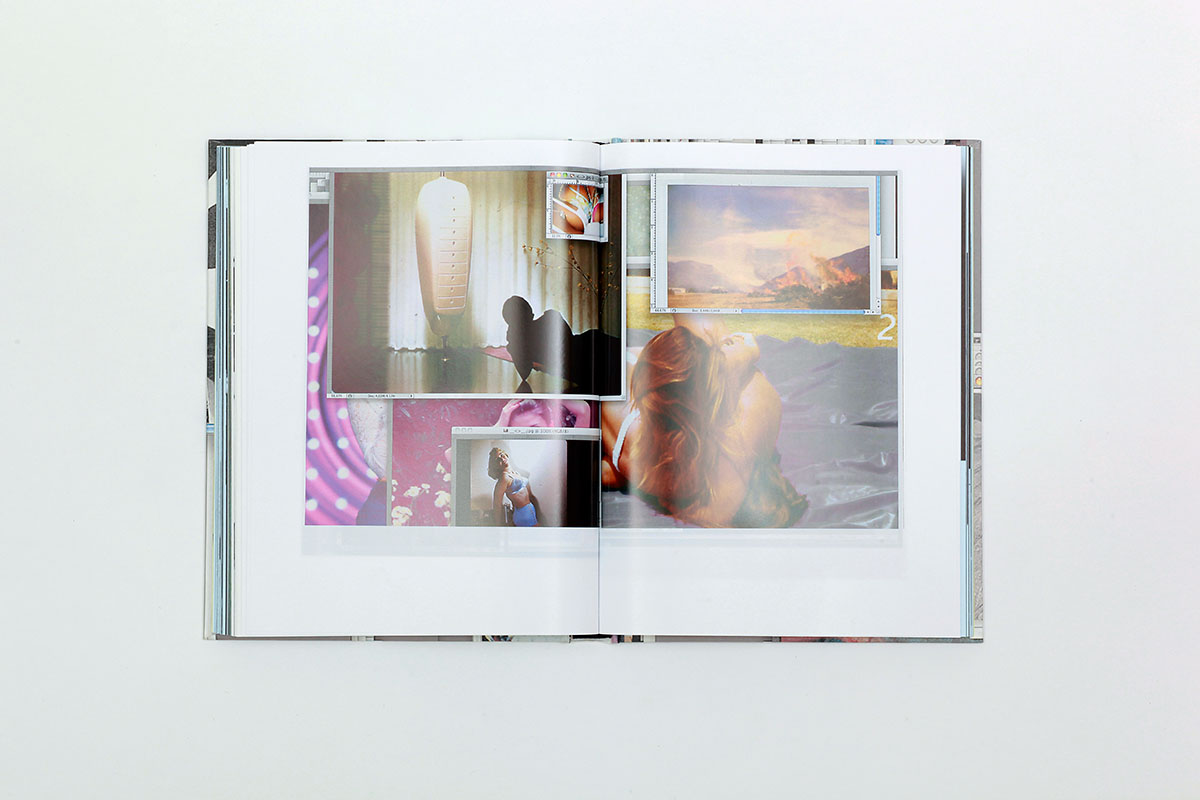

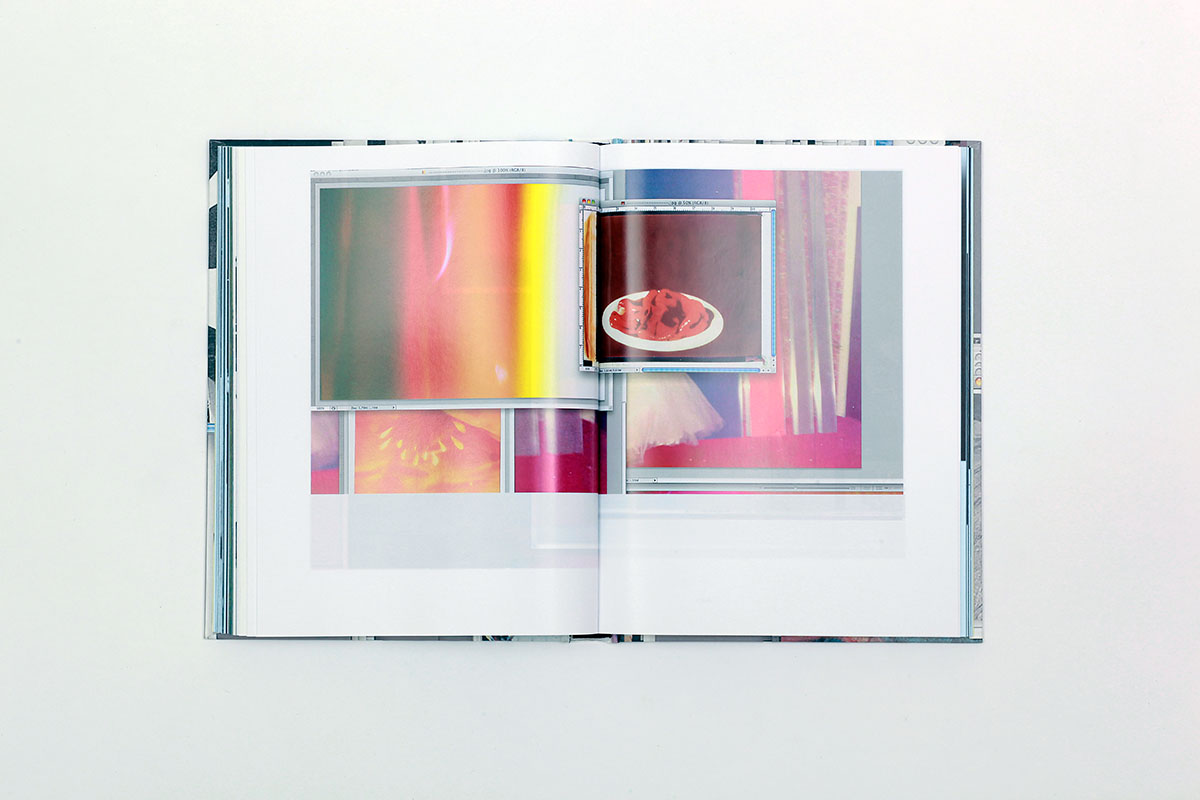

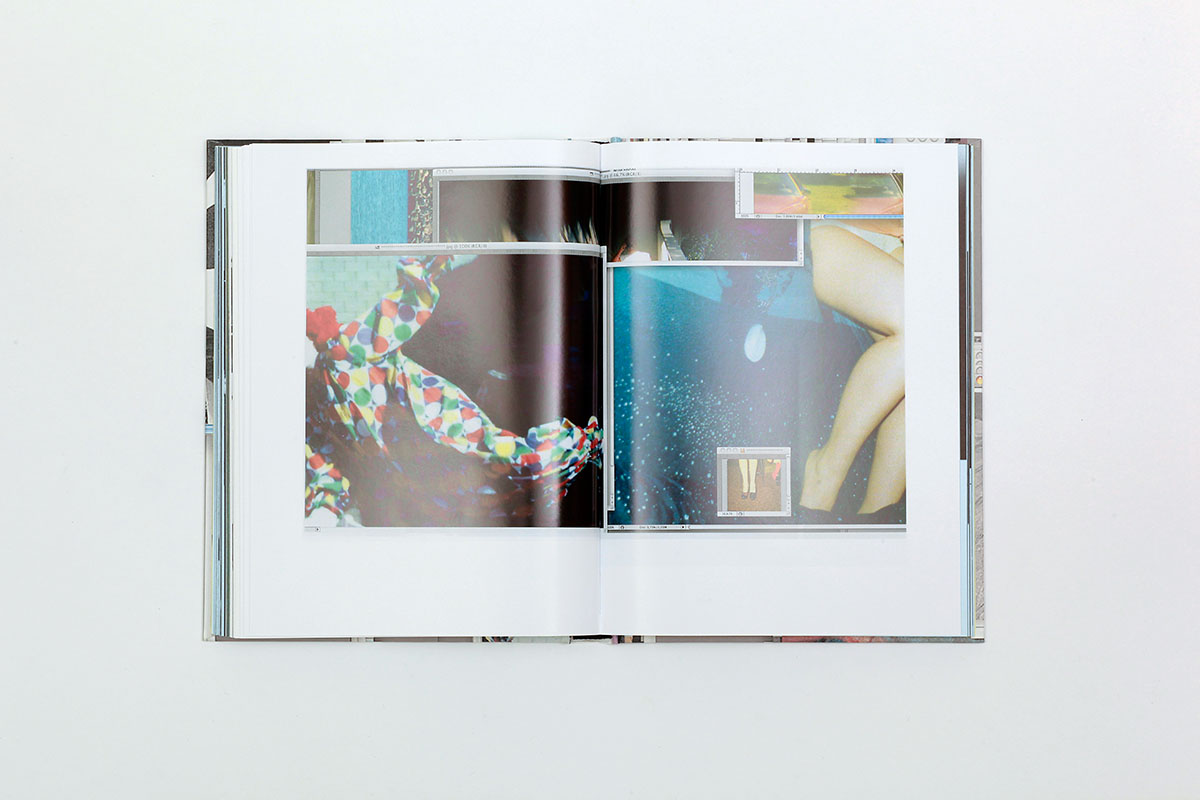

JP: In The Bungalow, it appears as though you are very assertively colliding a history of what appears to be manual collage with a much newer imagery/language of digital image editing softwares like Photoshop. Can you tell us about this?

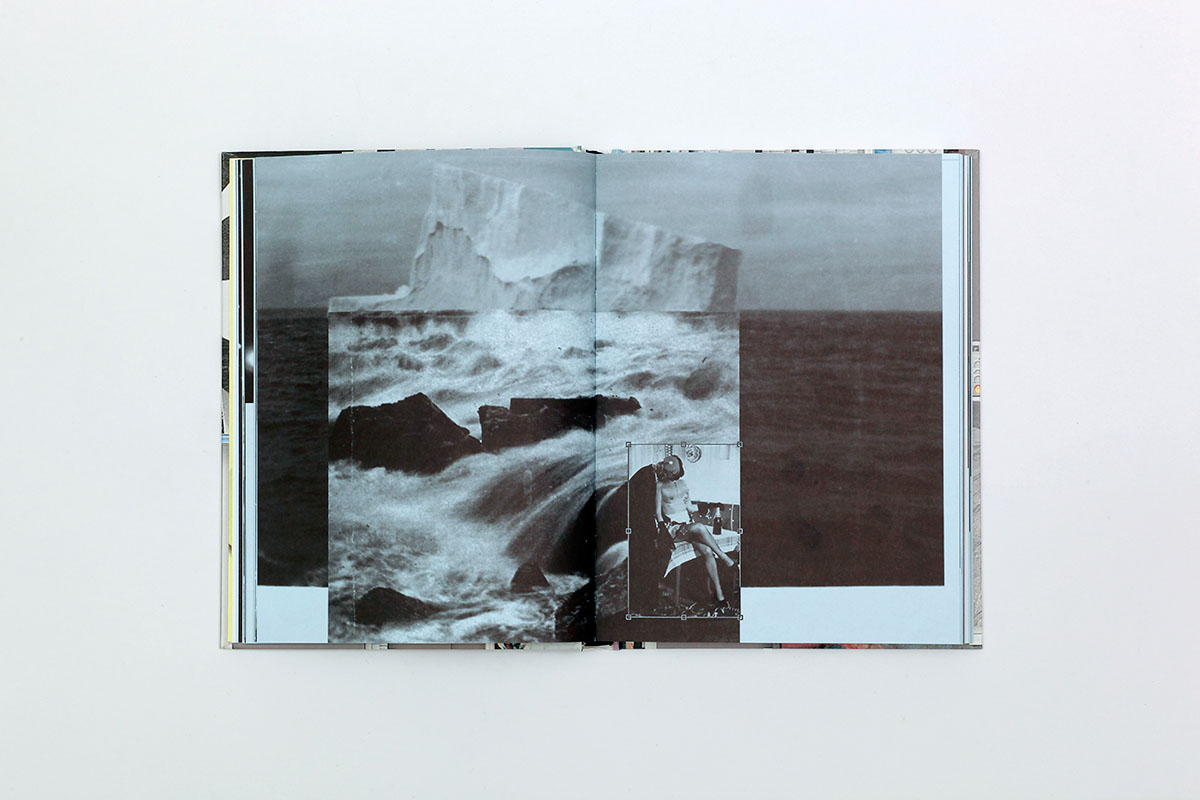

AK: Instead of the physical environment, the computer screen provides the frame in which you play with objects. Within this screen-frame, you slide the new entities (the photos) into, behind, and/or across each other. We do so consciously in Photoshop, or unconsciously by opening multiple photos or windows simultaneously. By making a screenshot of this compilation, you create a digital still life. A new entity comes into being, with its own origin on the screen (versus originating in physical reality). “Screenshot-photography” is born. In my view, this is a way to record the screen-reality in which we live.

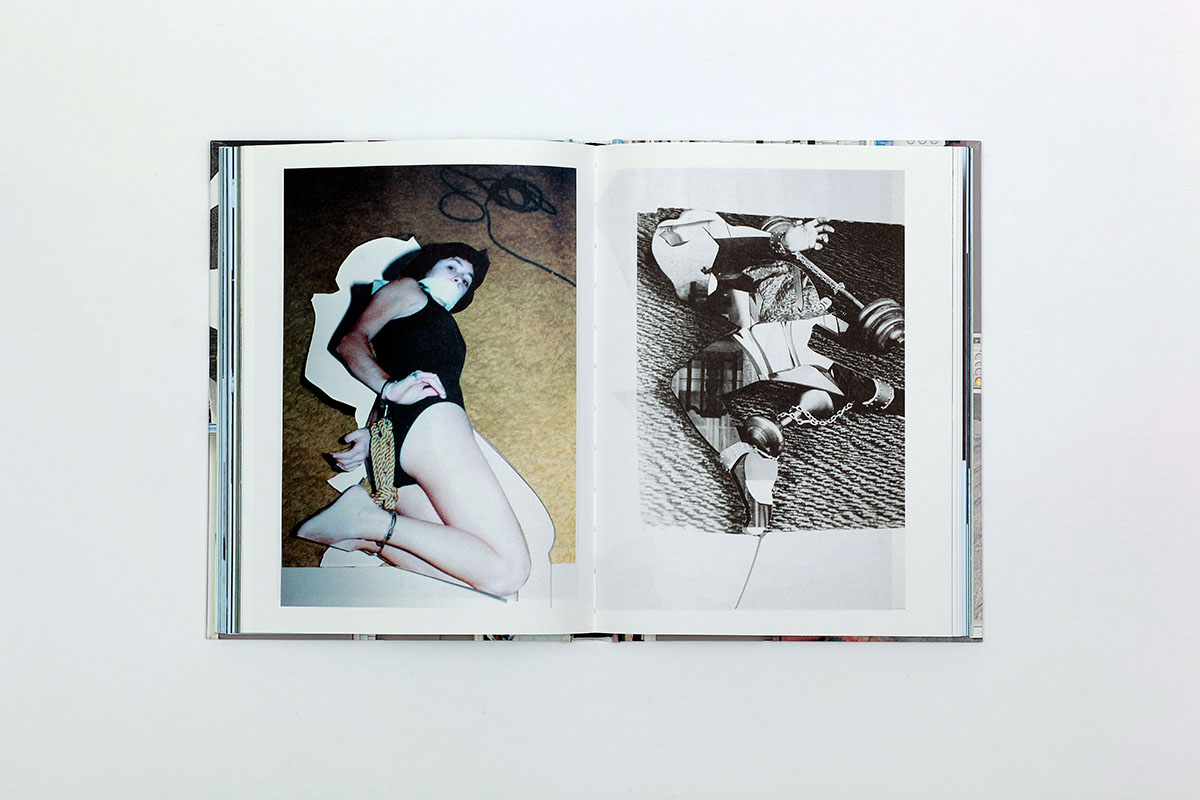

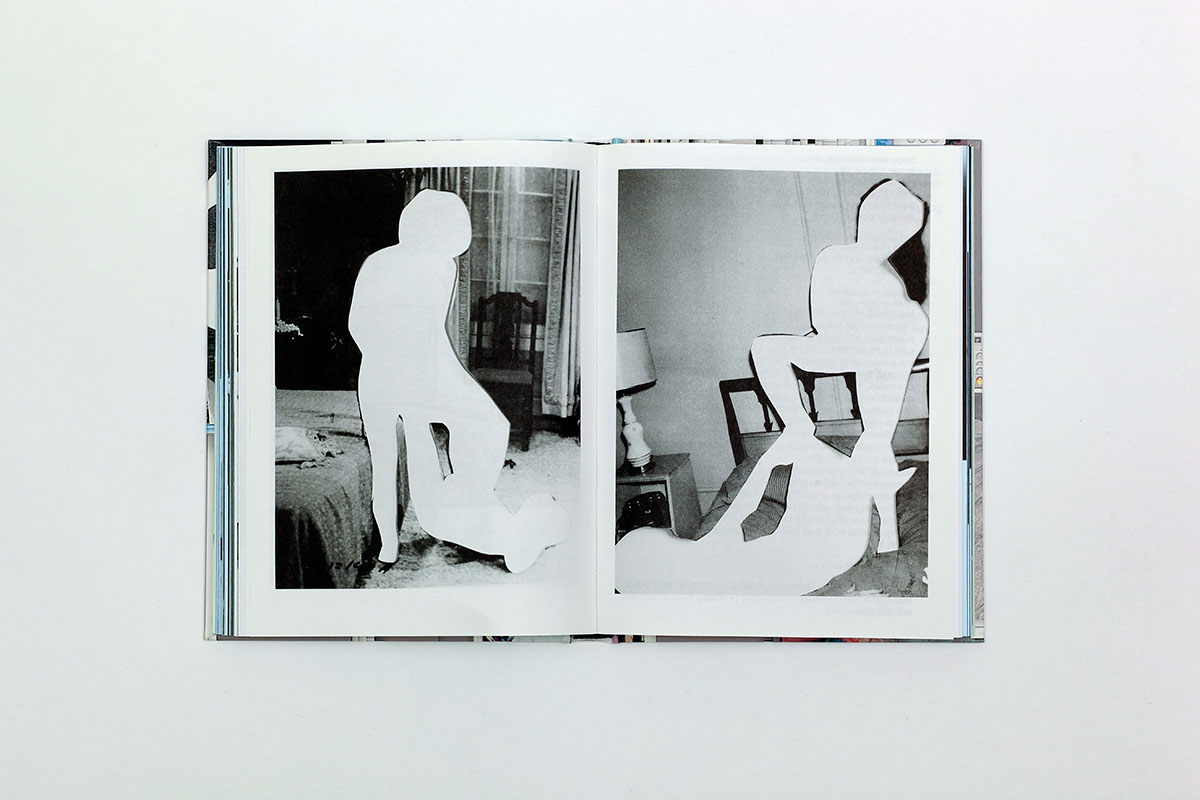

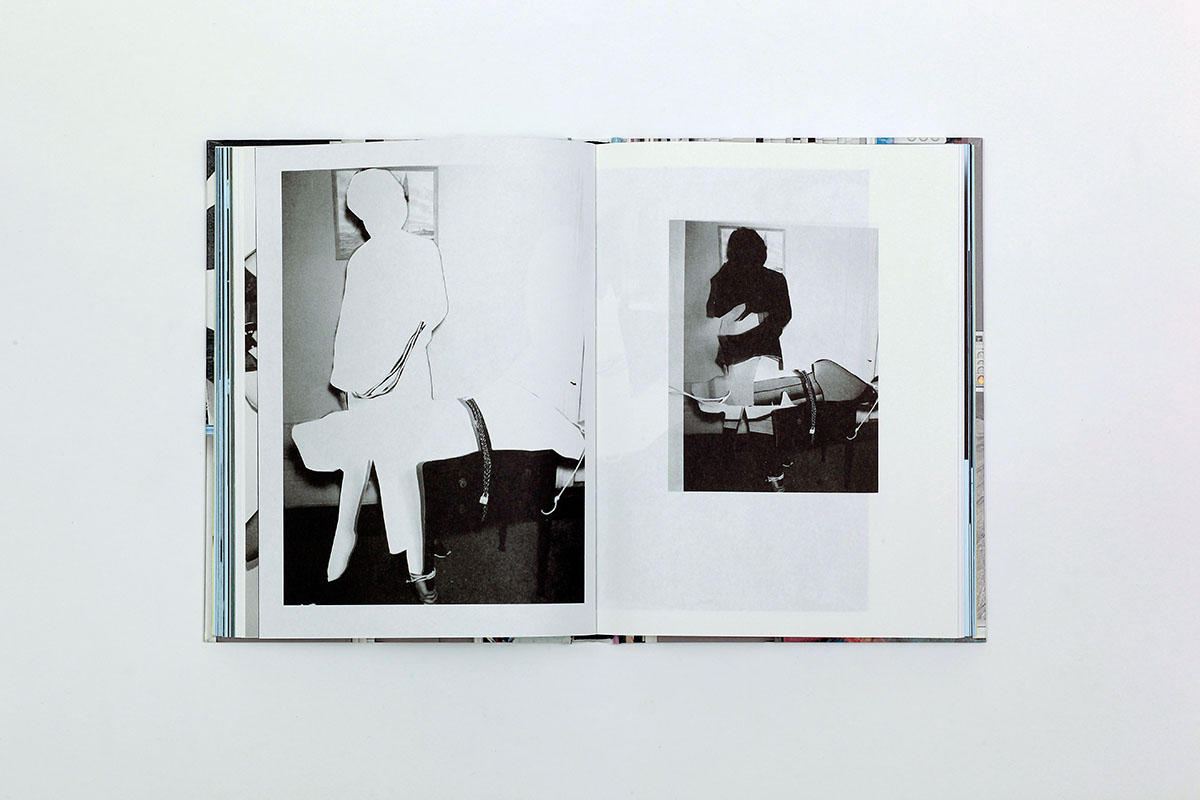

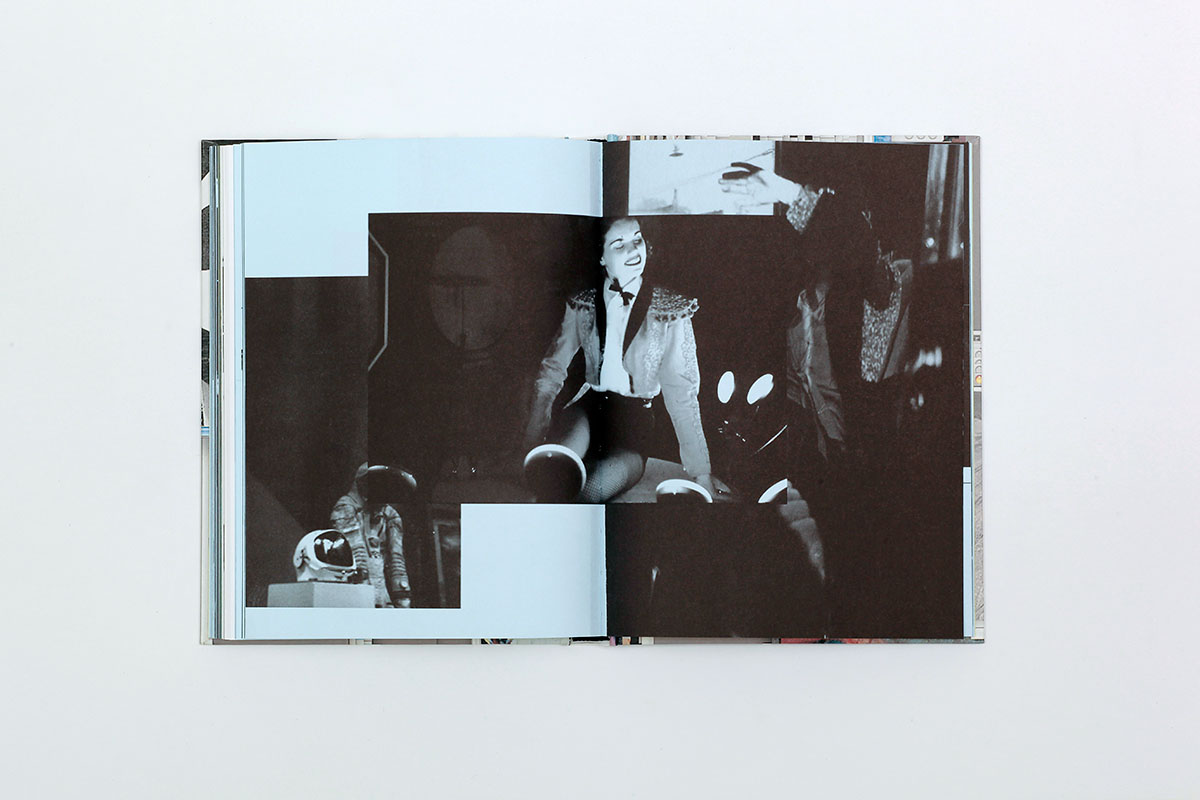

JP: I find myself lingering on the spreads in The Bungalow in which you are abstracting bodies engaged in what appears to be sexual or physical power play. Though you are abstracting specific content through the process of collage, the images of bodies performing through restraint, obfuscation, or other forms of manipulation persist.

AK: The bodies of those women are clearly acting some kind of scene between bondage and wrestling, and were literally cut out by my hand and a scissor. An empty void fills them up, their forms becoming sculptural. I find the forms more interesting. The imagination provides more to wonder about. Spectators are given space to visualize what they want to see or desire. I, for example see a white form vacuuming. But, actually, the vacuum was the body of a woman. To me this is funny and raises questions.

The white shapes let one focus more on the environment, the backdrops, and the furniture; rather than the acts those women are performing in the original photographs. Removing the women’s bodies also means relieving them from the previous situation. Maybe it was a power play before, but I don’t know. I wasn’t there when the pictures were taken. Neither do I know how those women felt when posing for those pictures. So I see it as a symbol of liberation.

There is so much female nudity in the history of photography, and often as a gesture of dedication and appreciation for beauty and female body. But to me it’s usually tiring, banal sexiness. Women are seen as objects to look at, and photos are sketches of surface.

This chapter does raises some questions about the position of women, the mystery, the funny side and the never ending intelligence, strength and power of women. At least that’s what my intentions and thoughts were.

JP: Your response makes me curious to ask if you consider yourself a feminist? Does that play any role in your art practice?

AK: Of course I am a feminist, which woman isn’t a feminist? Maybe the ones who don’t know what feminism means. Luckily, I am surrounded also by male friends who are feminist as well. I don’t necessarily manifest feminism through my art works directly, though, because I like to think about making work and striving towards a more holistic universe of equality. I feel that’s a huge task to think about. It’s what makes me depressed at times, like, “what to do?”

I have so much energy… what’s the richest and most valuable way to transition this energy for a bigger cause? But the thoughts are overwhelming and bring me in a deep dark black hole, because one can only do just a little. The best is to be honest to yourself. Do what you love and believe in this. Hopefully, it resonates when it’s truly sincere. Even if you don’t know what it actually is, you give what you can give. Bring it out there.

JP: Do you see the work you do as political? To me, presenting a critical, visual story divergent from more traditional or popular modes of presentation and representation (which you articulate above) could be interpreted as a political act. Was this ever your intention?

AK: My work is not political. Socially engaged, for sure. I strive to make rather layered work because I appreciate work which leaves space for people to engage with it by raising questions, leaving gaps, and intervening thoughts on different layers. It’s about respecting that people with different ages, cultural backgrounds, different emotions, and experiences will take something out of a work. What matters to them, what makes them wonder? My work isn’t a one way road with no space for u-turns.

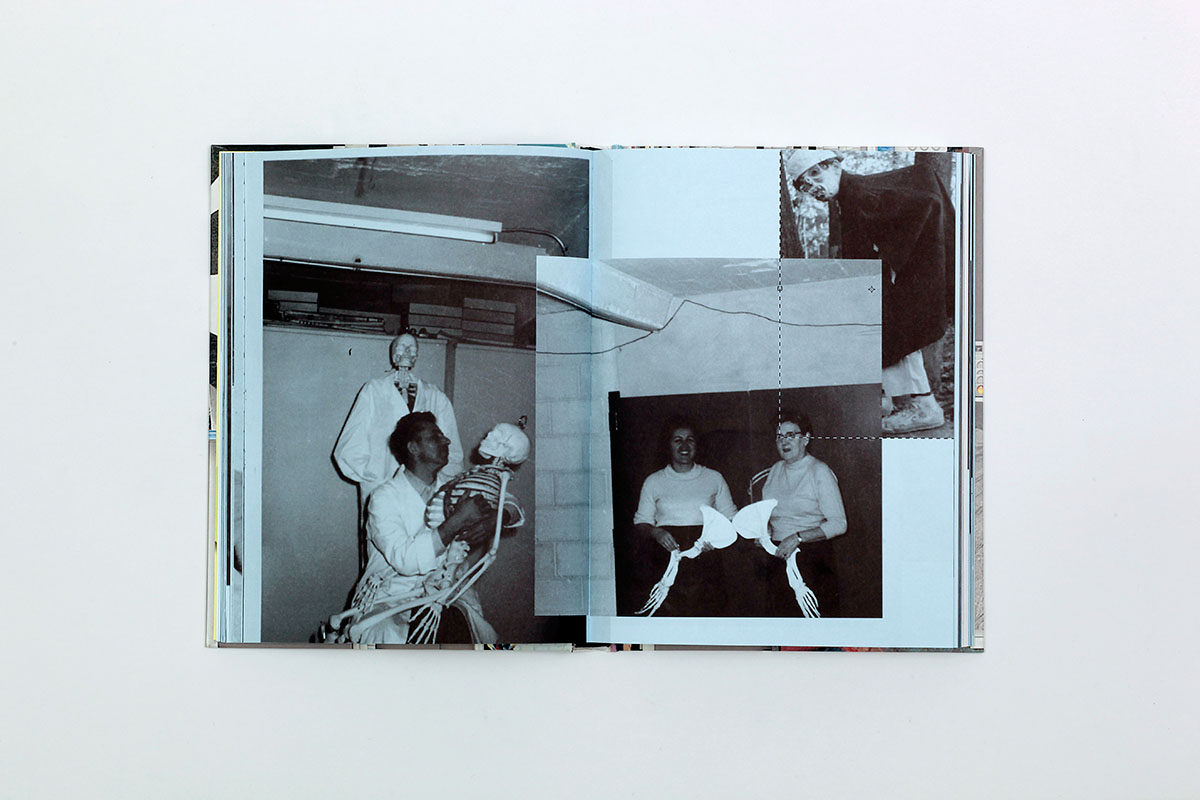

JP: I realize I’ve gotten a little off track, and maybe this is as good a time as any to make a u-turn to return back to The Bungalow. There’s something really sweet and strange about this spread with the skeletons. Can you tell us about it?

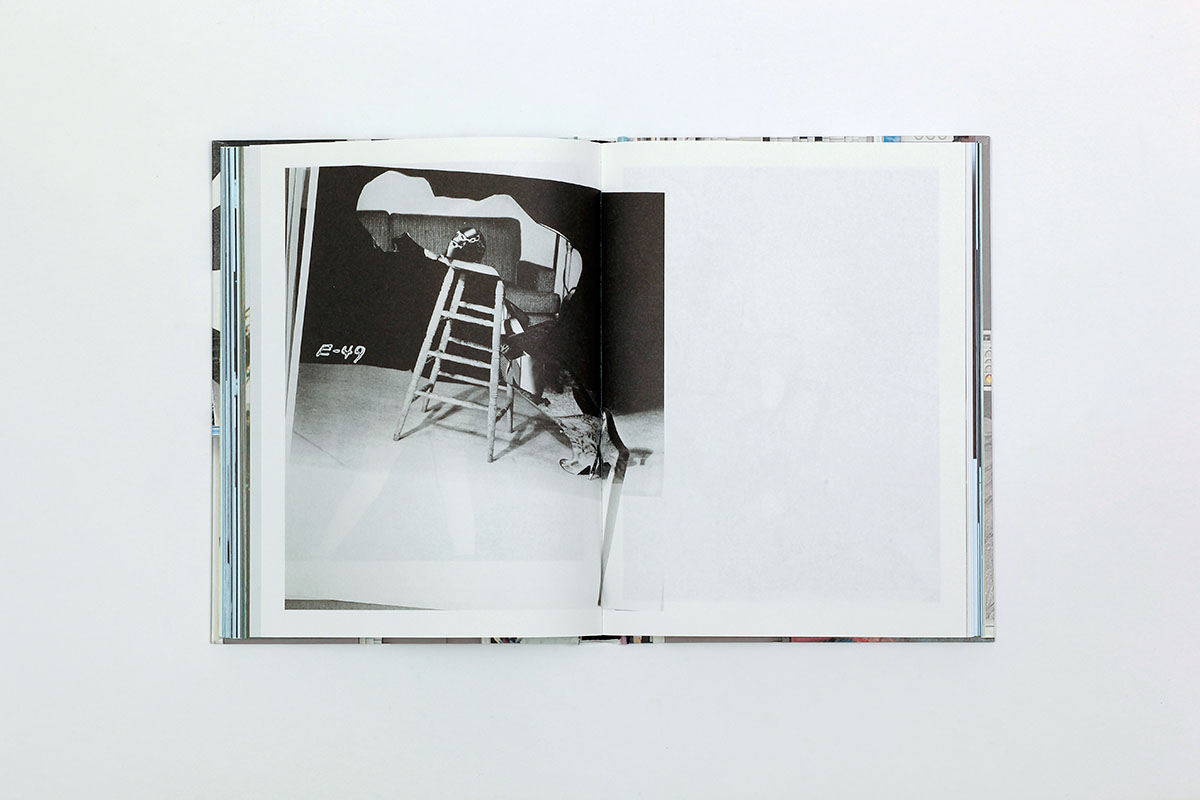

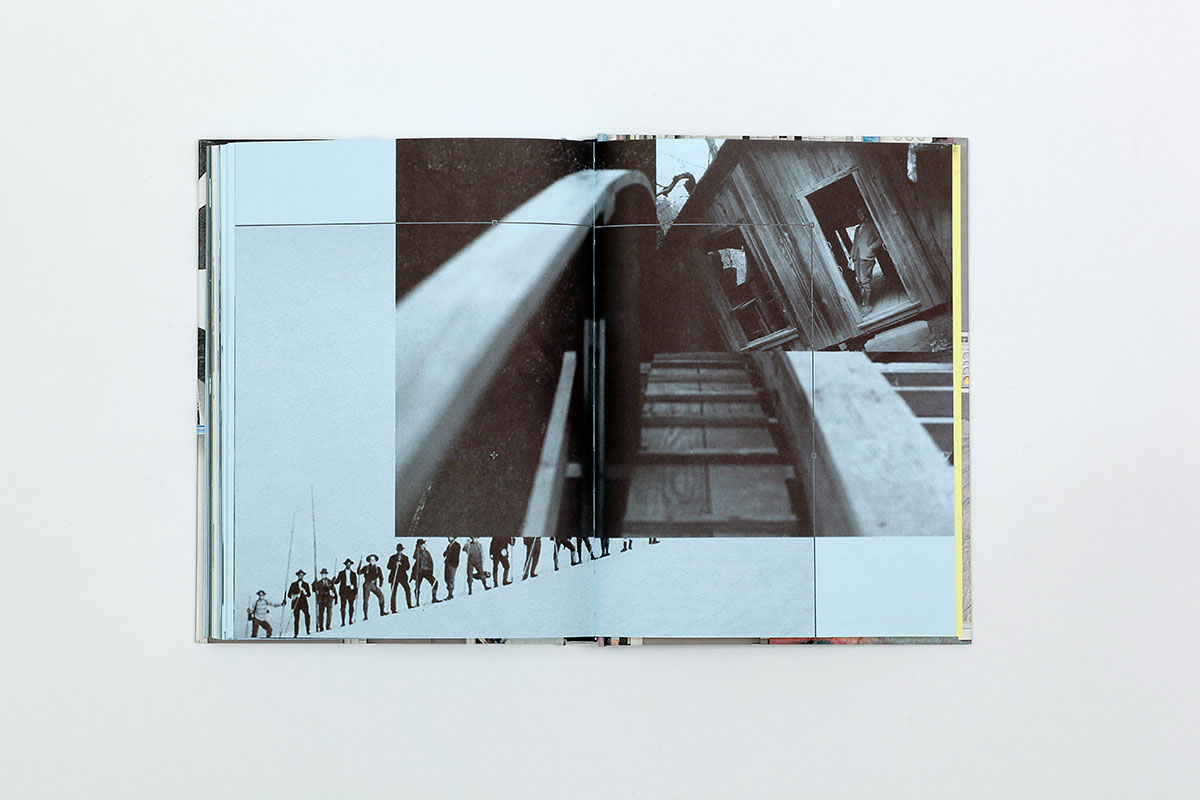

AK: From what I know about the photos I chose, those skeletons are the ones used in hospitals or classrooms in biology or anatomy lessons. It looked to me as though some people are fooling around with them in a basement, treating them as a real persona. The old ladies are laughing, the man dancing with them could be a doctor or biology teacher. They are just dancing with the skeletons, carrying them around. I think the people in the pictures are drunk. Those photos were probably taken by amateurs, and made me laugh out loud. I could not quite get how this situation would appear.

Isn’t that not the most interesting thing when you look at photos? They should be like question marks. That’s almost the only way I get hot from a single photo, if its embedded with some question mark behind the surface of what we see. Evidence by Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel is maybe the best example of what I’m trying to explain. Some of the images I chose from Brad Feuerhelm’s collection remind of, and relate to, that work by Sultan and Mandel.

JP: It’s almost as if the question mark, or that open ended unknowing, is your punctum which connects all of the images you choose to work with.

AK: If a photo does bounce this question mark towards me I have already passed by. There are too many photos. They are everywhere. One needs to develop a personal filter system to not drown in the image-ocean we’re living in.

JP: Are there any other chapters from The Bungalow that you’d like to tell us more about?

AK: Command Shift 3: New Photography is the chapter where you see some images opened in Photoshop and then re-photographed by making a screenshot. It’s a digital way of making a still life photo, screen-reality is a reality too. It’s like taking of a trip and stepping into some sort of parallel world. And like in a trip, I don’t want to see some images, while others enrich me.

I do not want an overdose of photos, and the abundance of photos must not make me forget the distinction between reality and screen-reality. Like a drug addict, I assume to have my photo-consumption under control.

JP: In looking at The Bungalow alongside your other books, it is easy to notice your incredibly vibrant and adventurous colors choices. Can you talk about how you arrive at specific palettes for each project or book, and what that decision making process is like?

AK: I filter life through color. Its broad pallet is brimming with strong mental qualities. This is most of all the case with indeterminate hues. While I mainly work with photography, I tend to manipulate, filter, order, and work with colour in ways that might seem to make more sense if I were painting or drawing. For example, Happy Birthday to You is printed on dirty mint-green paper because that is the colour I saw on most of the walls and in the isolation cells in the mental institution where I was doing the project. This color is supposed to have a calming effect on patients, although I think it might just be a placebo effect. When the institution was being set up, the powers-that-be decided to paint most of the walls this color. So, in this case, the specific color adds something to the project’s content. In Becoming Blue, I used blue because of its art historical and psychological meaning.

I deliberately remove color as well. The combination of black and white is a statement. Part of A Head with Wings is in black and white. A huge part of Happy Birthday to You is too, even though the images are printed on dirty mint-green paper. I also made a wallpaper diptych Der Ausbruch Einer Flexiblen Wand (hart/weich) in black and white.

I choose colors for specific reasons. Organizing things in color is a strategic way to create order within chaos, mostly because I’m always overwhelmed with material. I take too many photos and I’m an obsessive book collector. I always have too many things on hand. Working with color or non-color calms me somehow. It has a meditative effect on me and adds a specific aesthetic quality to the work. You might notice this more than I do, since for me it feels natural to work this way.

JP: Several times, you have used travel as a metaphor while talking about your work. It seems travel is a really important part of your life and art practice. How does travel feeds your practice as an artist?

AK: I love to be in the air, in the ocean, deep down under, or on the road. Movement is important. It’s what makes my life, and maybe my work, dynamic. My worst nightmare is to be a “real” studio-artist. I could never live/work within four walls, working only with materials and my own mind. That being said, I do need to work in a studio. Working with interventions on the street, traveling, interviewing people, and collaborating are important for my practice as well. Photography, video, and text make a connection with the outside world, which next to my digital persona, makes life interesting to me.

JP: If you could go anywhere in the world for any length of time, all expenses paid, where would you go, and for how long?

AK: What a question! I would love to be and work in New York, actually, this amazing place with people of all nationalities in it is unique. I feel it’s the place where this hunger for a more holistic universe of equality comes closest of all places in the world. The energy and drive this creates is fascinating and makes me not want to go anywhere else. But my visa expires mid-September, so maybe this plus my love (who lives in Europe) will make me move back. But I don’t need to think about this yet! I just moved into my new studio and have three interns coming to work with me until the end of June. I love being in New York. In this eccentric place, everyone is slightly insane.

JP: I always felt at home in the city when I lived there as well. Although, I do find that as an artist eccentric contexts crop up no matter where you land. So, what’s up next for you?

AK: Finally publishing my AUTOMAGIC book! I’m also developing my photo-sculptural practice, which will be shown at Art Bruxelles at the end of April. In September, I have a solo show with my gallery, but I have no idea what I will show.

I’m also working on a project around surveillance, anonymity, the representation of the self in media networked realities, and indexing/anti-indexing. It’s a huge collaborative project where I make simple photos of the back of heads of people posing against a simple one-coloured wall or piece of paper. It’s sounds boring, but it’s going to be thousands and thousands of pictures—heads becoming pixels. Brains and thoughts of people of all nationalities will be captured in there. Maybe it’s going to be statement on the failure of human encyclopedic unity.

JP: Thanks so much Anouk! One final question: What’s your favorite cocktail?

AK: The “Angelita” from the Experimental Cocktail Club, which is super close to my studio!

One of the most remarkable experiences in my life was diving the Cenote Angelita (a sinkhole) in Tulum, Mexico. You dive through a gas cloud hanging between saltwater and freshwater. When you’re lost in this gas cloud, looking up to the sun, it’s as if being in cosmic energy, as if the whole spectrum of color surrounds you, as if you’re breathing the roots of the tree. Once you go deeper through the other side of this gas cloud (~150 ft. deep), you see this bizarre set with a tree and the edges of sinkhole. It’s like caves surrounding you. It’s an outrageous experience. You have to walk with your diving gear through the jungle quite a bit too before you arrive, and you have to love diving and not be afraid of depth and small spaces. After the dive, you’d better smoke a little to emphasize the experience. I did this dive with an independent, hippie instructor who holds his gear in a van on the beach and we had a super high time together! When drinking the Angelita cocktail, I dive back in this memory.

JP: Thanks, Anouk. I, of course, want to encourage our readers to buy all of your books and check out your Kickstarter for AUTOMAGIC. I’d also love to encourage them to check out the wonderful video documentation of your books online. I love watching the way you handle the books.

AK: For me a book is an experience, an intimate meeting as well. I like to walk through a book with my fingers the same as how I explore the world traveling.

—

To learn more or support the publication of Kruithof’s AUTOMAGIC, visit her Kickstarter page.

Anouk Kruithof‘s work has been exhibited extensively throughout New York, Europe, Asia, and Australia. She has published seven artistbooks. She is the recipient of the 2012 ICP Infinity Award from the International Center for Photography and the winner of the 2011 Grand Prix Jury and Photoglobal prize at Hyeres, festival international de mode et de photography. Her work is in the collections of FOAM Amsterdam, Het Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Fotomuseum Winterthur Switzerland and Museum Het Domein Sittard NL, MOMA library, ICP library, Pier 24 library, and the library of Het Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

Jessica Posner is an artist, Communications Coordinator at Light Work, and Adjunct Faculty in the Department of Transmedia at Syracuse University. You can contact her at jessica@lightwork.org.