Re:Collection: M. Neelika Jayawardane on Zanele Muholi

Visitors to our website can now explore thousands of photographic works and objects from the Light Work Collection in a new online database that expands access of work by former Light Work artists to students, researchers, and online visitors. To coincide with the our new collection website launch, we’re introducing a series on our blog called Re:Collection, inviting artists and respected thinkers in the field to select a single image or object from the archive and offer a reflection as to its historical, technical, or personal significance.

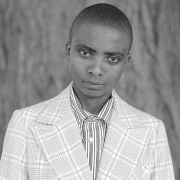

Today we’re sharing a reflection on Zanele Muholi’s Lerato (Syracuse), 2015 from M. Neelika Jayawardane, Associate Professor at SUNY Oswego and Light Work board member.

Zanele Muholi’s work has always focused on telling stories that were rarely incorporated into the national narrative, or South Africa’s celebration of itself as a newly democratic nation. As a “visual activist,” Muholi’s portraits provide the foundation for her remarkable, long-term cartographic project, Faces and Phases. This portrait series, created between 2007 and 2014, maps, “commemorates and celebrates the lives of the black queers” Muholi met during journeys that spanned rural and urban South Africa. The project also collects first-hand accounts that bear witness to the schizophrenic experience of living in a nation where LGBTI people are often the targets of violence—this despite the fact that South Africa’s progressive constitution specifically protects the rights of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Intersex (LGBTI) people. Having realised that not having photographic evidence of her maternal or paternal grandparents resulted from a “deliberate” erasure, Muholi remembers feelings of “longing, of incompleteness, believing that if I could know their faces, a part of me would not feel so empty.” That knowledge of deliberate, systematic erasure from the nation’s historical records is so acute that she is driven now to “project publicly, without shame.”

We recognize, today, that ethnographic and tourist photographs serve the function of aiding Western visitors’ creation of subjectivity—as superior, perhaps benign, socially, intellectually, and geographically mobile, and participating in the flows of modernity. That project of European modernity required that the African subject remained firmly “fixed,” immobilized in time and place. Given that history, Muholi’s image of Lerato Dumse, a writer who documents their travels together for this project, reminds us of the significance of black portraiture photography—photographs of black subjects by black photographers—in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. As with W.E.B. du Bois’American Negro installation for the 1900 Paris Exposition—which organized 363 images into albums—Muholi uses photography and portrait-making as powerful political tools that contribute to one’s self-perception, as well as to the ways that others visualize who you are, as an individual or as a social group. Muholi’s work also signifies an older tradition of African studio photography, in which it is plain that those within the frame—people who colonial administrators and contemporary travelers from the geo-political West often misrepresented and caricatured—are no longer satisfied with remaining as simple “subjects.”

Today, there is a proliferation of photographs of black people, and in particular of black, African people, by white photographers. It is not just an “absence” of images that Muholi’s work helps counter, but an over-abundance of a problematic gaze that has its roots in white supremacist ideologies. As photography scholar John Edwin Mason recently wrote on Twitter, “White people like to look at photos of black people. There’s a seemingly insatiable demand [for] photos of black folks. Part of the reason is that photos give us permission to stare.” Though we “all like to stare,” he argues, audiences in the geo-political West have historically liked “to stare at the racial other.” Whilst some of that looking can be borne of somewhat benign curiosity, and even accept and celebrate the challenges that Muholi, and other black women and non-cis-gendered photographers pose, much of what we continue to reward in portrayals of African people is what Mason calls a “safe” gaze. That photographic gaze allows the “looker” who is geo-politically situated in the West to remain in a comfortable, traditional role—wherein they are entitled not only to look, but to penetrate, and to impose. It does not “disrupt established ways of seeing—and, thus, knowing—black and brown people,” or “take viewers outside of their comfort zones.” Because of the “safety” that such portraiture affords white viewers, especially, Mason concludes, it does little to challenge or change ways “of seeing and knowing that are the product of societies in which white supremacy is a given.” Though such photographs are often attractive (mostly because they meet stereotypical expectations we have been trained to imagine as “African”), and technically and compositionally expertly-made, they also fail us by presenting our world in solely heteronormative terms.

That failure of imagination is what this remarkable photograph by Muholi—and Lerato Dumse’s seemingly simple, direct look-back at us—counters. Here, Dumse is a powerful, playful co-creator of their portrait. They are self-styled, moving between phases in mood, in dialogue with the photographer and potential audiences.

The photograph gives us permission—perhaps even invites us—to stare back at Dumse’s lovely, symmetrical face, and their choice of slightly oversized check-pattern jacket, paired with an unlikely shirt patterned with bold, vertical stripes. But we know that we are not driving their narrative, or simply instrumentalising the person in the frame of the photograph as an “other” to further our own subjectivities. Rather, we commune with them with a respect and an understanding that this person is able to powerfully fashion themselves and how they wish others to see them. They are in dialogue with us, looking back and pushing back against the narrow possibilities that hegemonic culture made us all believe is all we have. This portrait gives us—all of us— the courage to ask for far more.

Find more of M. Neelika Jayawardane’s work online here.

Explore the Light Work Collection online at http://collection.lightwork.org