Odette England Dairy Character Interview

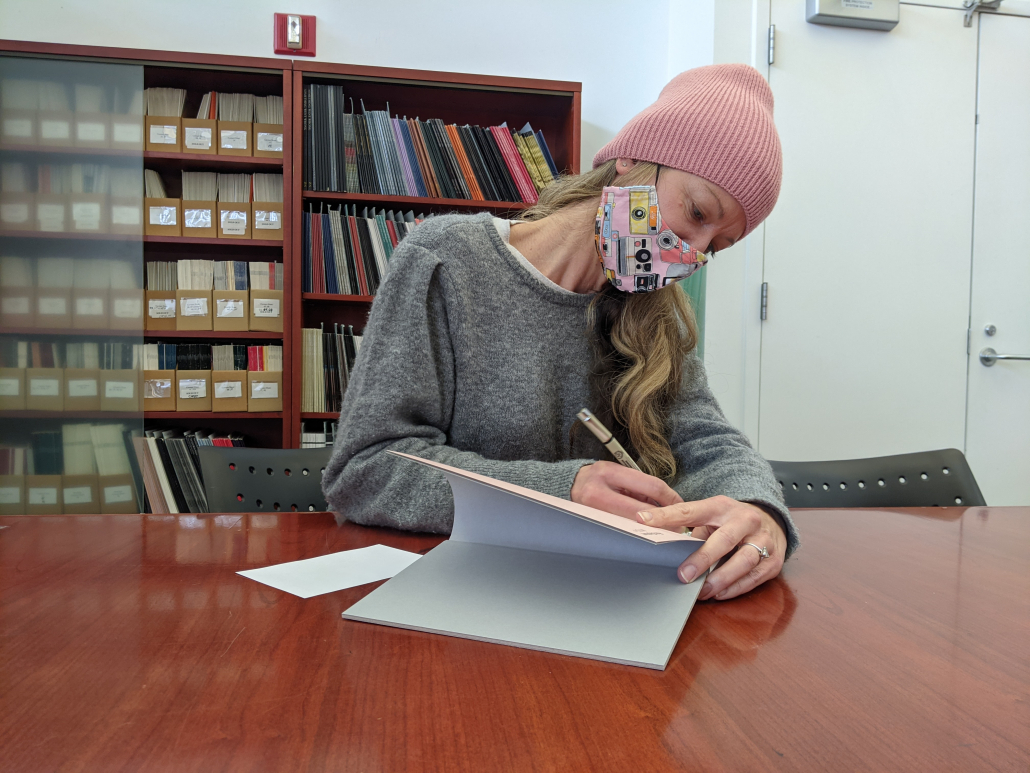

Holiday Gift Idea from Light Work! Signed copies of Odette England’s Dairy Character are available for purchase in our shop! Orders must be completed by December 15, 2021 at 11:00 a.m. EST to ensure your gift arrives in time for the holidays. Purchases made after the deadline will be shipped after January 4, 2022.

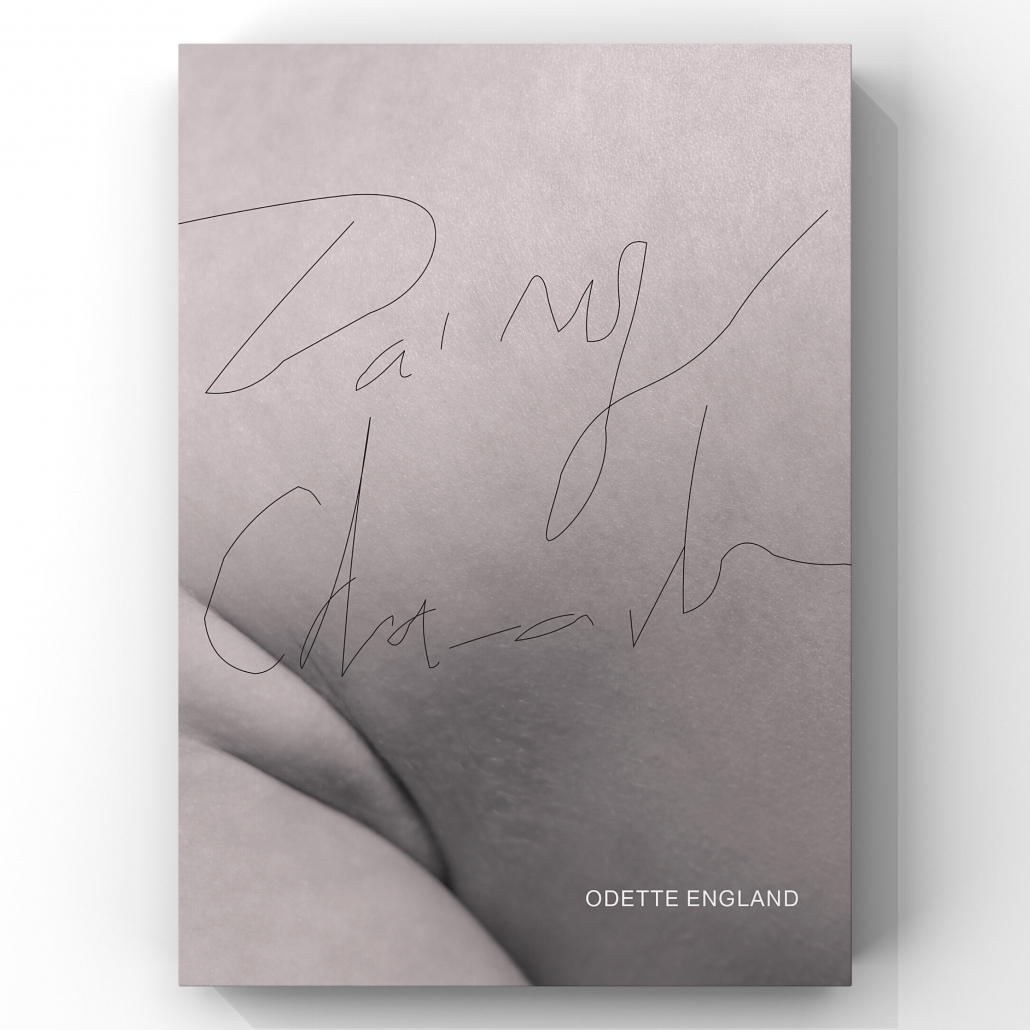

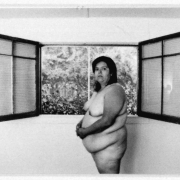

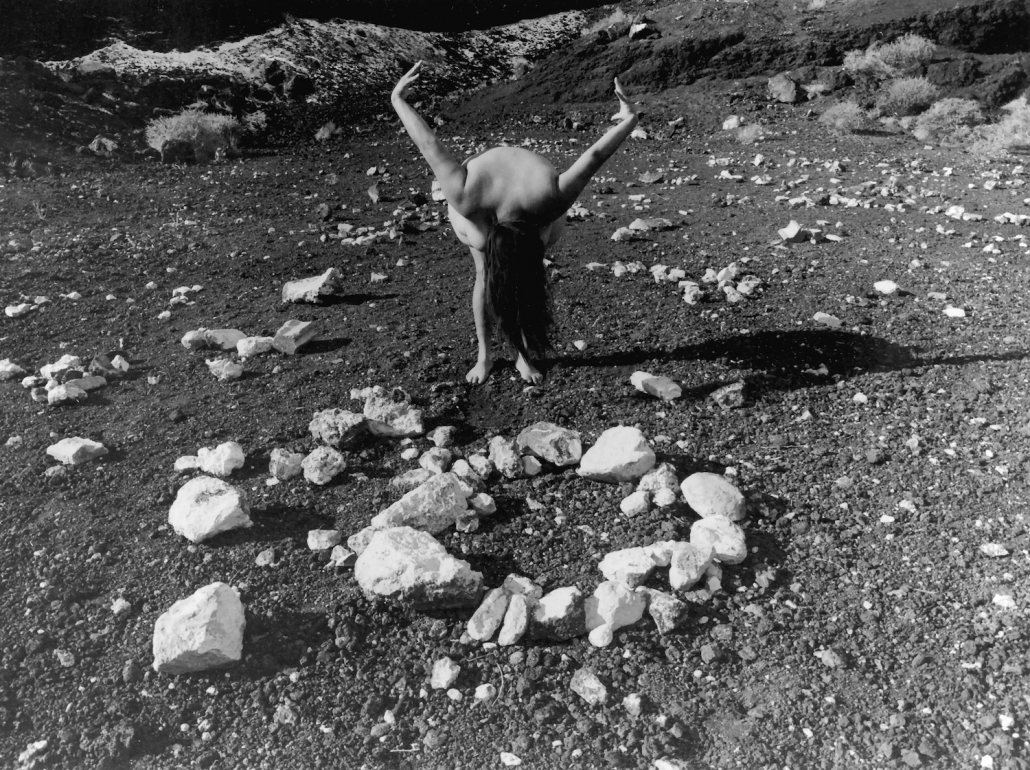

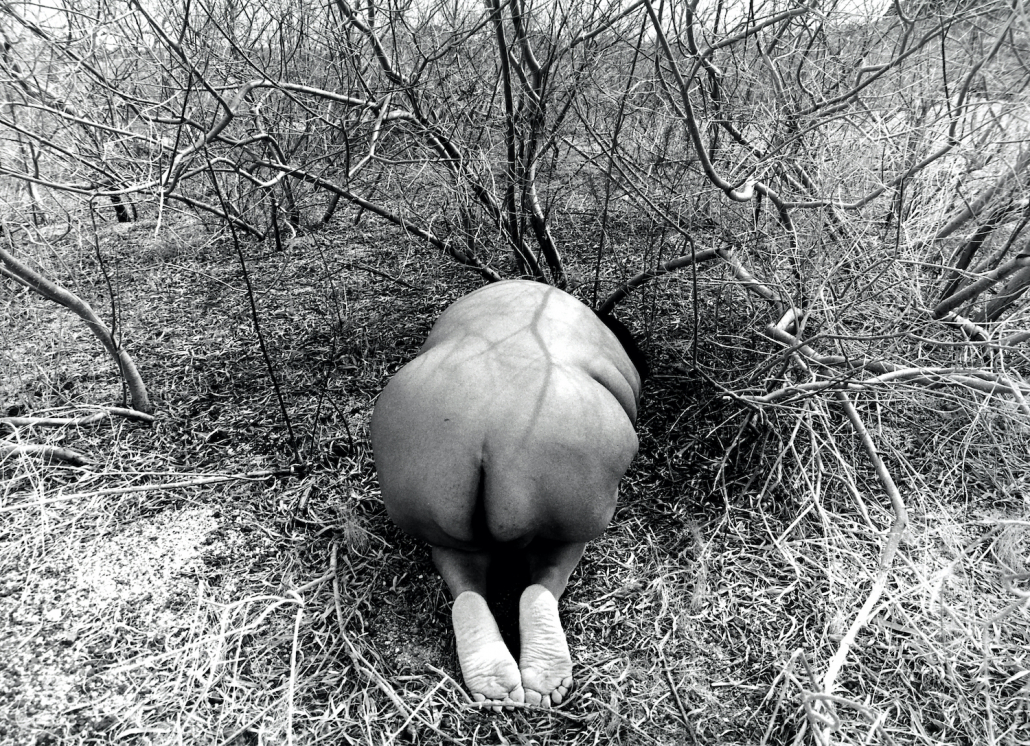

In her latest book, Dairy Character, photographer Odette England delivers personal insight into the life of a woman growing up on a dairy farm in rural Australia.Expressing the importance of shining a light on girls and women in rural areas, England draws a staggering comparison of the objectification of women and dairy cows. (Russell, Grace, Musee Magazine, September, 16, 2021)

The images are reproduced in delicate tones; England also interlaces blush-coloured papers in the book. But the content is uncomfortable, centring on extreme close-ups which suggest a reductive way of seeing both cows and women. It is a subversive look at the literal and visual language of farming. (Smyth, Diane, British Journal of Photography, April 16, 2021)

—

Sydney Ellison (SE): — I just wanted to say that I loved the book and I was so excited to get a little sneak peek at it when I was at Light Work. So first, I wanted to know if you could share a little bit about the manual that you found that inspired the project and what it was and how you reacted to finding it?

Odette England (OE): Sure. So I was visiting my parents. They now live in the town where I was born and I was going through when they leave the house. I turn into a little kid and I start rummaging around in cupboards and looking for secrets and photographic inspiration and things to enjoy looking at and reading. And in this cupboard in a box, I found my dad’s old cow manual and every registered dairy farmer receives a copy of this manual. It’s not exclusive to Australia. Lots of countries have these cow manuals and the idea is that they’re given to the farmer as a way to help the farmer rank and assess the physical strengths and weaknesses of their dairy cows. So they do that by focusing on two things: they focus on the production of milk and the breeding production of calves and they call it “dairy character.”

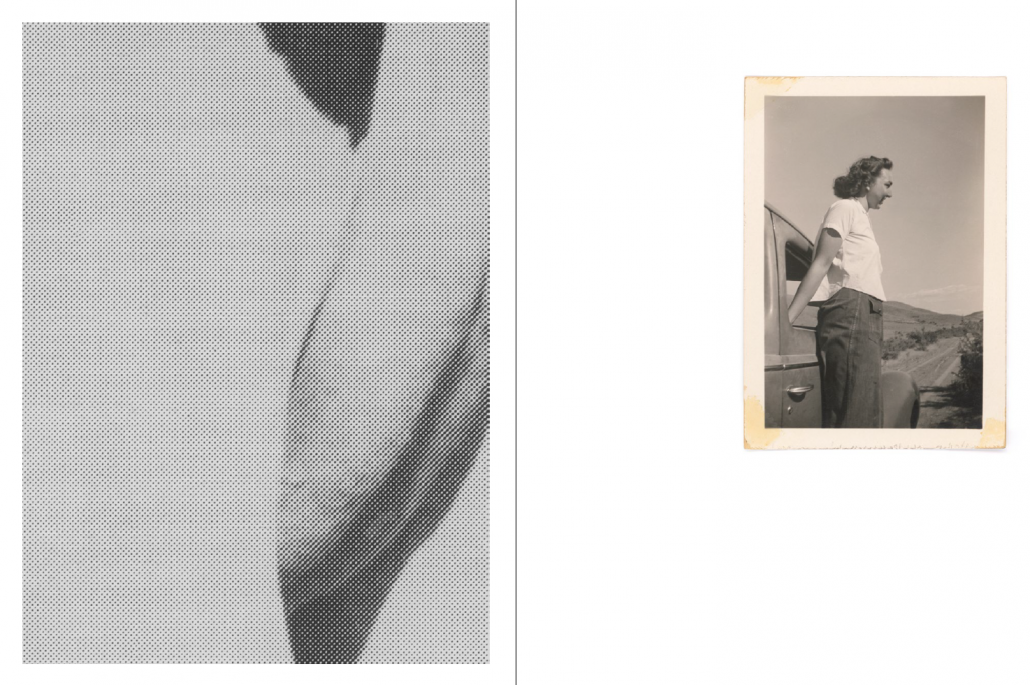

When I think of someone’s character, I think about writing a character reference. I think about someone’s morals and values and what kind of person they are. But for a cow, when they talk about dairy character, it’s entirely about quality and quantity. It’s the quality of the milk they produce and the calves they produce and the quantity, how much milk and how many good calves. This book is very plain. It’s black and white. It’s written exclusively by men. It’s half text, half images. The photographs are very low quality, but they’re extreme closeups of the bodies of cows. So you see utters, teats, legs, vaginas, bottoms, anything that speaks to a cow’s ability to make a lot of milk and produce a lot of calves.

But they’re very grotesque images because they’re so visually, physically violent and they’re almost too descriptive. It was a very quick look that I had through this manual. I remember my father having it. He kept it in the second drawer of his filing cabinet, which was always locked. And I remember seeing it from time to time as a kid. So coming across it and looking through it, I felt like I’d found something wonderful and terrifying and curious and problematic, but I’d also found this foundational piece for work that I’d been making for five years. I had all these little prints over my studio wall in New York City and I couldn’t call it a project. I couldn’t call it a series. I couldn’t call it anything other than images that I’d been making or images that I’d been asking my parents to make on my behalf. And when I found this manual, suddenly I had the foundation and the framework and the bodily object of a book, a structure that made sense of all of these pictures that I’d been making for the longest of times.

SE: That’s amazing! Like the idea that sometimes you just have to wait, and then the practice is contextualized. I’m really interested in the way that this project brings up criticism in the ways that visual and textual language can reflect each other and influence each other. As well as the way that both of those things shape our perceptions of everything around us. And I’m familiar with this type of criticism in photography, which reinforces how photography can be exploitive. So I thought it was interesting that you brought in the ways that this happens with farming and specifically with female cows. So I’m wondering if you could talk a bit about how you think both verbal and visual language influence our attitudes towards people, places, and ideas and how you think they maybe overlap or how you think they differ?

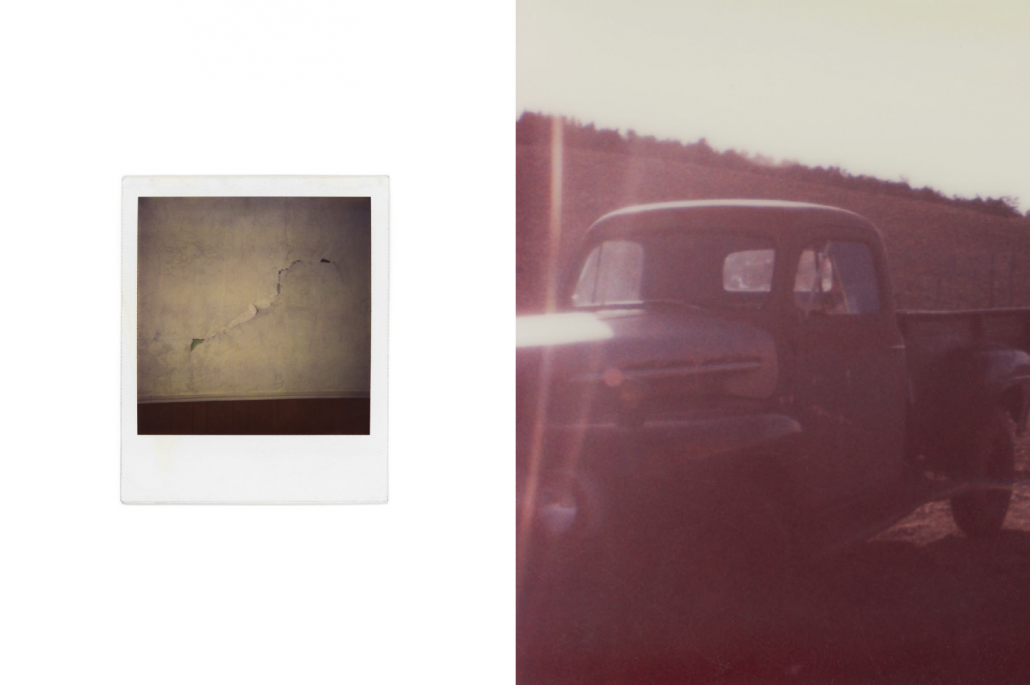

OE: Okay. So I’ll start by talking about just within the book itself. There’s a mix of images. There are images that I’ve made. There are images that my parents have made under my direction or instruction from the cow book that they lifted directly from that. So they’re archival pictures, and then there are family snapshots and then there’s writing from myself, maybe 18 or 19 short stories, each about 300 words, that sit right in the middle of the book. There are photographs that illustrate those stories, but they’re not included in the book. So I felt from early on, there were ways in which I had to tell this story through different kinds of photographs and through different forms of language. And some of that language needed to be storytelling, specifically autobiographical storytelling because the images didn’t support the story or illuminate the story in the way that words could.

And then there were images that I felt had to be included because the story around or behind them was ineffectual. So I feel like photography is great at showing things, but also terrific at excluding things because it’s always a crop and it’s always a subjective decision. But words are like that very much too. But possibly going back to, if I’m understanding the question correctly, is so much about growing up in a male-dominant community and particularly a rural farming community is it’s a life about gesture and it’s a life about nonverbal communication and it’s a life about communicating with your body. It’s about the simplicity and the economy of words. Farmers don’t use adjectives, right? They don’t over-explain anything because they don’t need to. And it’s similar to the way that I understood and grew up making pictures, that they were economical, functional, clinical.

They were not meant to be voluminous. And they weren’t meant to suggest other things outside of themselves. And so even in my writing, in the book, I’m very, very direct. And there’s not a lot of fluffiness around the words. And so I’ve tried to do the same thing when I was making the pictures as well. Even in choosing the photographs that went into the book, I very specifically chose images that have a kind of tactile value to them. They look and feel like what it was to grow up in that environment. They look dirty, they feel rusted, there’s bent corners. I’m pointing to physicality, not just in the subject matter, but in the actual objecthood of the image itself. So that idea of tactile values was super important. You know, they had to look a bit haphazard. They had to look a bit disheveled. They had to look like how a female body was regarded and considered and treated within this community, that it was a body of labor. It was a body of secondaryness. I’m not sure that’s a word, but they were secondary to the men. And often behind cows as being these heralded beasts, these heralded bodies.

SE: For a good amount of my life. I grew up in a very rural area. Neither of my parents went to college. So art school is a very different environment. And I’m wondering how you navigate bringing up this topic that is specifically contextualized in working class and rural experience to an audience that most likely doesn’t have the same complex understandings of your community and how you show that it goes beyond just being about “these people” or this community’s prejudices.

OE: I think some of that comes around to how women in contemporary society are still secondary bodies in many situations. And the way that I often come at my photographic practice is to speak autobiographically, but it’s always with a kind of awareness of things that I still experience now because rural life in Southern Australia, in this tiny community in the 1970s through the 1990s, is so removed from me now, let alone anyone else, that I had to find a bridge. And a part of that bridge came through photographing my daughter and looking at the way that she’s now 11 years old, but I’ve been photographing her for this project not knowing it was a project, not knowing that I was photographing her for this since she was five. There are kinds of behaviors. There are kinds of ways in which the female body is looked at, judged, picked apart, assessed, considered both by humans, looking at bodies, but by photography, looking at a female or female-identified body, and those ways still persist, although the ways in which we society do that has changed and has moved.

And I don’t want to say move forward because that implies a positive direction. I’m just saying it’s moved, but there are still the same issues that I think women or female-identifying bodies and faces experience. And that became something that was important for me to include in this book. It couldn’t just be about a rural community. It couldn’t just be about farmers beating their chests and saying, “We are dominant. We are the gods and there are the animals.” And then there are the women. It had to speak to the kinds of labor that women still perform, for the most part, without being paid for, let alone recognized for it. Diane Smyth at the British Journal of Photography sent me a wonderful article from the New York Times, which spoke to the idea of the pandemic’s influence on females and female-identified persons and how their lives had changed almost backward from having to perform a kind of role of woman or perform a kind of female identity that was expected, anticipated required of them. That wasn’t something I was thinking about when I was putting together this book, how the pandemic was cause this.

SE: So you talked a little bit about why it was important to include your daughter in the work and I’m wondering if you could talk about your choice to include your parents in the work and the process of making, rather than just the subject matter, such as why that was important, and what their response has been to the project.

OE: I started asking my parents to re-perform my past in around 2010. I was here in the US in grad school, and I wanted to nurse myself back to health, or nurse back to health this place that we loved and lost, this dairy farm, in 1989 owing to near-bankruptcy. And my way of doing that, because I couldn’t travel back, was to have them go back to a place that was their career, their labor, their great love, and have them re-walk this land over and again, every month for an entire year. And I would direct them where to make photographs. I would ask them to go back to the family album and find pictures of my younger brother and I, and to remake those pictures. All the while I’m sending them back to a place of pain, a place they couldn’t sustain that couldn’t sustain them.

It’s a perversely psychologically damaging request, but it is a request that a parent would understand. If my daughter was asking me to do the same thing I’d say, yeah, no hesitation. And then also about what it means to have some kind of parental custodianship over decision-making to help your child, to help a family member. So I didn’t feel like I could talk about this place. I mean, I never owned, my parents never owned, this place. The bank-owned our home, this place that they started off sharecropping, I couldn’t talk about it without including their voice. I couldn’t talk about it without including the years that they spent trying to make a life, trying to make a living from soil, from things outside of their control. Because a farmer’s life is almost entirely governed by things like the weather, which we have no control over.

And I was trying to control it through photography, which we assume we have some kind of control over. But actually the reverse, I think, is true, that we can’t control it no matter how much we think we’re in control of a device in front of our eyes. So I felt like their voice was really important to that and that some of the pictures in the book that they had made that I couldn’t make. Sometimes I write as me. Sometimes I write as my father, sometimes I write as my mother. So there’s this slippery use of language and storytelling where, you don’t know whose voice it is, but they sort of overlap a great deal, as do the photographs too. There’s this overlapping of past and present and growing up, all happening at once. So it was this very layered way of looking at story.

My daughter was a participant in this. You know, it’s a very collaborative process. There were pictures I made of her that she insisted I didn’t use. There are pictures that I made that she felt had to be in the book, her understanding of it. If she was uncertain or uncomfortable about anything, I didn’t include it. You know, she’s not a muse, she’s not a model, she’s her own person. And so it felt really important to include her in that process, but also to make her monumental. Like I spend a lot of time photographing from a really low angle. I wanted the female body to stop being this thing that was bent over and hunched over for labor where the faces isn’t seen, although there are images where I’ve cropped the body off, like the cow manual crops bodies off. But I also wanted to herald her like that Alexander Rodchenko series, Young Pioneers, where you are looking up at the majesty and wonder and joy of someone being thought of as magnificent and not just being a body, but being something that feels and emotes and has energy and passion, and fear.

And so, a lot of the photographs of Hepburn—that’s my daughter’s name in the book—speak to that. She’s like a sunflower, kind of, looking for the sun.

SE: My last question is just that, besides having grown up in different circumstances, what ways do you think your daughter might experience the issues of this work differently than you? Or I guess, even speaking to growing up in different circumstances, if you have ideas as to how she relates to it differently?

OE: That’s a good question. And a good question for her. When I go back to the farm, which I try to do every year—though since the pandemic started, I have not—she comes with me and it’s usually my mum and my daughter and I who go back. We have this ritualistic behavior that has become apparent over the last five, six years since Hepurn was five years old. We go back to the farm. We have to ask permission from the owners to walk the land. It’s been through, I think, nine or ten owners, at least since 1989. And in the past six years, it’s been at least two different owners. So there’s this ritual of having to ask permission to even go there. Hepburn goes there with a child-like, inquisitive joy of experiencing farm life through a few hours of visiting.

And she thinks it’s the most magical place on earth, right? Because what she sees is what I saw—there’s soil and there’s trees to climb, and there’s hay bales to make cubbies out of. And there are still animals there. There are animals to pet and fences to climb over. And, you know, a stick becomes a sword or a wand. Everything is steeped in fantasy and magic because it’s not like an everyday life. For me, you know, I had a 200-acre playground. So for me being outdoors was not only this wondrous place of play, but it was also a place of imagination. It was a place of education. How I learned color, you know, yellow wasn’t yellow, yellow was canola or alfalfa or canary or egg yolk. The way that I learned things was through these 200 acres. For her, it’s so much fun.

And because she loves to pretend, she would do these things. She would pretend to be a cow and be walking on all fours through where the old dairy was. And I would just photograph it for fun, not thinking it would be part of this, but it was interesting to watch her behave as I had once, absolutely benignly and innocently about the wonder of place, which is how I was. But when I look retrospectively at the photographic evidence, at the oral storytelling, the difference between the oral histories that my father would tell versus my mother would tell, the kinds of rules and restrictions my mother had, and the role that she had to enact in that community versus the freedom that my father had. It’s only upon becoming an adult and a parent myself that I can look back at those things with a loving eye, but also a much more critical eye.

So for Hepburn, it’s still this magical, wonderful place. And she looks at these images from the cow manual and says, “Wow, they’re strange!” Or she’s aware to some extent of what she’s interpreting what she’s seeing, but certainly probably not in the way that I’m experiencing it or revisiting it because that was my life. And her life is a city life. And one where she lusts after something that seems so wonderful. If I told her we were moving back there tomorrow, she would be immersed with joy. But the reality of how that life would be very different because of what it means to be remote. How do you get to school? Where do you go shopping?

SE: Thank you so much for talking with me and congratulations on the book. It was so much fun to talk about this.

OE: Thank you.

—

Sydney Ellison is a Brooklyn-based artist whose work addresses themes of gaze and intersectionality primarily through collage and self-portraiture. Ellison is an art photography student at Pratt Institute and an editor of The Photographer’s Greenbook, a resource hub for Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Advocacy within the lens-based art community.

—

Internships at Light Work

Offered year-round, Light Work internships provide a platform for undergraduate and graduate students to gain practical, hands-on experience in our exhibitions, education, and collections departments. Light Work’s programming includes exhibitions, educational classes, workshops, community education programs and initiatives, residencies, publications, a digital darkroom, and a library. We endeavor to match each intern with duties that match their interests and learning goals. To apply for internships fill out our Internship Application PDF and send it and all requested documents to lab@lightwork.org